By Loreen Berlin, Special to the Independent

By Loreen Berlin, Special to the Independent

Twenty years ago this month, a savage fire devoured 14,000 acres of Laguna Canyon wilderness and ravaged multiple neighborhoods.

The fire that destroyed 391 homes and threatened more than 1,000 others at the time was believed to be the work of an arsonist, but the perpetrator were never found. Investigators collected evidence statements, received 480 arson leads and ruled out non-human causes, but investigators were never able to determine who started the fire.

“That’s the frustrating part of our business; often the fire destroys evidence,” said Scott Brown, division chief of the Orange County Fire Authority, which investigated the blaze because it ignited first in county territory.

On that fateful day, Brown was a fire captain and one of the first arriving engine companies, No. 222, on the scene in Laguna Canyon.

Investigative reports on the Laguna fire of 20-years-ago were purged, according to Brown, as records are required to be kept for only seven years.

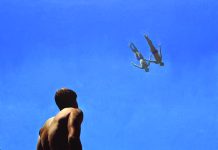

While the “cold case” arson may never be solved, the impact on human lives that dark day in Laguna history can be measured in other ways: police evacuated 27,500 people; 306 fire engines were on scene along with 25 hand crews; 19 bulldozers plowed fire lines; 19 air tankers took to the skies dumping 60,000 gallons of fire retardant, according to a report on the blaze to county supervisors by Larry J. Holms, then director of fire services. In all, 10 helicopters joined the operation alongside 1,968 firefighters. There were eight minor injuries.

Water-dropping aircraft, which could have made the fire manageable during its first 15 minutes to hold and keep fire from advancing, was not available because of 20 other blazes burning around the region ignited earlier and drawing upon those resources, Brown said.

“We cannot stop fires from happening; the natural beauty of California’s wild lands coupled with periodic extreme weather conditions provides a perfect storm for wildfire. We can do our part to fight these fires. But we also need the public to do their part,” explained Brown.

On Oct. 27, 1993, the temperature was 80 degrees by 8 a.m. Santa Ana winds howled at 40 to 50 mph, sucking humidity from the atmosphere and fanning temperatures, a dangerous combination that fuels the rapid spread of a wildfire.

Brown’s fire station received a call as part of the Red Flag protocol, asking them to patrol part of the El Toro and Laguna Canyon roads, an area known as the wildland-urban interface, looking for any potential fire problems.

“We have a high state of readiness during these conditions; our goal is rapid initial attack of any wildfire. Patrolling that area in the morning, we returned to the station. No sooner had we backed the engine in, than we were notified of a vegetation fire,” Brown said. Five callers reported a brush fire at 11:50 a.m. near Laguna Canyon Road, according to Holms’ report.

Looking west from the 5 freeway, a large column of smoke alerted them the fire was “moving out.” “We knew we had a significant event,” Brown said.

They entered Laguna Canyon Road where Battalion Chief Steve Whitaker, who is nearly 7- feet tall, raised his hands above his head, waving them to stop. “You need to try to flank the fire and keep it from jumping Laguna Canyon Road,” Whitaker said.

A plea for air tankers, made just 18 minutes after the blaze was reported, would not be answered until 1:40 p.m., delayed by priorities from numerous fires burning elsewhere, Holms’ report says.

Against those odds, the fire out-stripped the ability of firefighters to hold the line and began firing operations, a strategy of fighting fire with fire. Despite that effort, the fire could not be contained.

“The fire was like a freight-train racing down Laguna Canyon Road,” Brown explained. “We tried to find a good anchor point to flank the fire, as you never want to be in front of a fire; everywhere we looked we saw a wall of fire and flame,” he said.

By 12:28 p.m., the fire split, moving toward El Morro school and mobile home park, Emerald Bay and Laguna Beach as the wind blew harder and flame heights increased to 50 feet. Weather stations clocked hurricane-force gusts of up to 92 mph and the fire burning 100 acres per minute, Holms’ report says.

At 4:03 p.m., with the blaze having consumed 5,000 acres and 44 mobile homes and 49 homes in Emerald Bay, the fire suddenly jumped the canyon at Big Bend, a curve in the canyon road where flame lengths reached 200 feet, Holms report says.

As high winds swept the fire into the Mystic Hills neighborhood, the incident command center retreated to Main Beach from Thurston Middle School, where 12 classrooms burned, and fire crews were re-deployed to the Top of the World neighborhood, where firefighters made a stand against the onslaught of the fire, Brown said.

Top of the World resident Gene Felder said the fire was “hit and miss” as to which homes survived; i.e. a home with a shake roof, akin to fire-kindling, didn’t burn, while a home with a new tile roof, supposedly more fire-retardant, burnt to the ground.

Felder recalled a description of the blaze by the late Claes Andersen, who lost his home and his wine collection in the firestorm. Andersen said when fire advanced within 150 feet of a home, it would suddenly erupt from within.

“The fire conditions were dynamic with tender, dry explosive fire conditions,” Brown said.

What has changed in those 20 years?

“We’ve had significant residential development in fire-prone areas,” Brown said. “Now we need to have homeowners better involved in preparing against the threat of wildfire.” As well, fire authorities need to engage people to take preparation measures, he said.

On the operational side, OFCA has established its own helicopter program. Two state-of-the-art helicopters have been added to the firefighting arsenal. The helicopters can drop water with pinpoint accuracy and they have rescue capability, he said.

“We have the opportunity to save lives and to arm citizens with information to better prepare for the threat of a wildfire,” Brown said.

Loreen Berlin may be reached at [email protected]

I remember someone commenting about the heyday’s of Timothy Leary in Laguna Canyon, that if you remember those days you probably weren’t there.

And even though it is good to remember our past so to prepare for the future. There still is a sense of remorse in those that suffered the emotional trauma and loss of physical possessions on that day.

The Missionary 17th century Jesuits wrote with cautionary tale advised travel around and avoided the canyon lakes because fire breathing dragons lived here.

Anthropologists that have excavated cave dwellings of early native Americans here believe only cave entrances that faced south were used as established settlements because the same fire danger existed then as it does today.

Only those who saw first hand what transpired are able to tell you what we witness was something really unexplainable

because it seemed to be fueled by not only the ground and the dry vegetation but the air itself.

The same flames that were over 50 feet high shrank to 2 feet

when not in the direct path of the wind.

In hindsight all the geographical areas that did not burn were known ancient gathering places and settlements.