Carrying on Her Mission in Nepal Despite Setbacks at Home

The author in the village school funded by donors to Laguna's R Star Foundation. By Robin Pierson, Special to the Independent

Rosalind Russell may be homeless and facing financial ruin here, but in Nepal she’s a heroine.

Over two years ago, “the goat lady,” lost her home by fire and is in litigation with her insurance company over rebuilding it. Her personal funds are diminished and she’s living in a one-room pool house, thanks to a friend’s generosity. But in over two dozen rural Nepalese villages, Russell is credited with giving hundreds of women opportunities to elevate their lives and the lives of those they love.

Because of Russell, women who barely had a chance to even touch money are now earning it. Children whose opportunities for education were dismal now attend classes at a newly opened “Top of the World-Nepal” school. Mothers and grandmothers who never thought they would learn to read, now attend literacy classes, while others who once could only dream of starting a small business are making candles, incense and clothing.

On a recent trip to Nepal, I saw and heard first hand from the women Russell has impacted. And I got to meet, Rabindra Sitaula, Russell’s “adopted son” and the other half of R Star Foundation, a multi-faceted non-profit organization determined to decorate the impoverished Nepali countryside with goats, schools and fresh water.

In villages perched up rocky roads and down dusty trails, where Nepalis struggle just to get the basics for life – enough to eat, access to clean water and medicine when they or they children need it – I was treated like royalty, simply because I knew the Western woman responsible for providing opportunities for them to get what most of us take for granted.

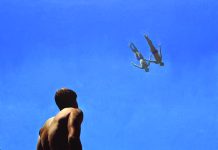

In dwindling light, the setting sun turning the ice white Himalayas rose, our battered taxi approached the hill top village of Palanchowa Sathighar. After waiting for hours, dozens of women and their children jumped to their feet, clutching necklaces and bouquets of brilliant orange and red marigolds, excitedly welcoming Sitaula and me.

Villagers shower Rabindra Sitaula, Rosalind Russell’s “adopted son” and the author with flowers for the life-changing gift of goats that the pair’s non-profit brought to their village.

A beneficiary of Russell’s and Sitaula’s goat giving project Maya, a middle-aged woman wrapped in a sky blue shawl, moved to the front of the throng. Badly burnt as a child, never married and without family, Maya – which means love in Nepali – had inhabited the lowest rung of her village’s status ladder. Now Maya’s standing has sky rocketed, for she was the one who brought Russell – and her life-changing goats – to her neighbors.

Six years ago, Maya approached Russell and Sitaula when they stopped to rest at a nearby resort. She told them how two women in her village had just died in child birth because they couldn’t afford to stay at – or even get to – the hospital, an hour’s drive away. Maya told Russell and Sitaula that while many villagers want to send their kids to school, they can’t afford the government tuition, about $50 a year, not including books or uniforms. And when money is scarce, as it usually is, Maya said, it’s the women who go without food or medicine.

Maya had heard about the goat giving the pair had done in neighboring villages. Would they, she asked, consider her village? Russell and Sitaula had their next challenge.

Two and a half years later, goats came to Maya’s village – via pickup truck filled with the animals and the women from a distant village who had raised them. All villages that receive goats from R Star must agree to pass goats forward to a different village in two years. And the goats delivered to Maya’s village, were the progeny of R Star’s first goat giving project, begun in Wojethar, the village where Sitaula was born.

As darkness enveloped Palanchowa Sathighar, the women showed me those first gifted goats and the throngs of others that had sprung from that original offering. Squatting beside a tethered female, one woman wrapped her arms around the four legged creature’s neck, grateful to the animal that had made it possible for her to send one of her children to boarding school.

Another brought out the candles she had made; the fruit of one of R Star’s many collaborations with local organization to bring cottage industries in the villages.

And then there was the gray haired woman who, speaking through Sitaula, told how she had thought herself to old to learn to read and write. But when Russell’s non- profit began offering literacy classes in collaboration with local Rotary Clubs, she went. Now, she is one of the best in her class, and will soon by one of the 1,400 who have already graduated from the program, breaking the cycle of illiteracy in a country where the majority of women and about half of the men are illiterate.

What began as an improbable relationship between a compassionate Nepali boy and a plucky Western woman has transformed into an enduring and powerful partnership.

Sitaula and Russell met 22 years ago on the streets of Kathmandu. He was 11 and attending boarding school since there was no school in his village. And she was a glamorous doctor’s wife on a global spiritual quest.

“I practiced my English with her and she came to my boarding school and saw my room, Sitaula recalled. Russell invited Sitaula, and his uncle, just two years his senior and also a student, to her hotel, a five star establishment, the likes of which the village boys had never before set foot in.

After that first meeting, Russell and Sitaula began corresponding. “Those letters really helped me,” Sitaula said. “There was a true sense of sharing. We used to write quite a lot about the world, life, and our stresses. She wrote long letters.” For Sitaula, lonely at school away from his family, and for Russell who was going through a divorce, the correspondence deepened their relationship – and it continued for years. Five years into their letter writing, “I began calling her mom,” Sitaula said. Once email arrived, the month or more between correspondences shrunk and the communication between the two flourished.

In 2003, 15 years after their first meeting, Russell decided it was time to see her “son” in person. Russell wanted to give Sitaula and his family a gift that had meaning. And it was that initial intention that propelled Russell and Sitaula onto a path that has impacted the lives of thousands living in the desperately poor Kavre district of Nepal.

“I used to write to her about how we bought goats for our festivals,” said Sitaula, a Hindu. But when Russell struck on the idea of gifting Sitaula’s family a goat, she ran into an obstacle. Sitaula, then a manager at a radio station, lived with his family in a rented room in Kathmandu. They had no room for a goat. But he knew people who did.

Situala brought Russell to Wojethar, the multi-caste village, where he grew up without running water, electricity or a school. Nothing had changed since Sitaula moved to the capitol, about a 3 hour drive away. Women still spent hours each day hauling water from a river of questionable cleanliness and the majority of the children did not attend school. “When Rosalind saw the hardships,” Sitaula said, “she was willing to take on hardships of her own to ease the villagers’.”

After researching similar projects and speaking to government officials, the pair plunged in with their goat-giving scheme, giving women in Sitaula’s village two pregnant goats each, with the condition that within two years, they “pay it forward.”

They couldn’t have started their project at a worse time. The Maoist insurgency raged, finding ready sympathizers amongst rural villagers who had received little or no help from the government. The pair attempted to remain neutral as they travelled by motorcycle through the warring countryside, contacting both the insurgents and the government security forces before they ventured out.

“At that time Nepal was very scary,” Sitaula said. “The Maoists were trying to get rid of Western influences. Rosalind used to say, ‘If I die, burn me atop a mountain. Don’t put me in a polluted river.’”

The pair persevered, bringing goats to village after village, with those villagers, passing along pregnant goats to their neighbors. The result: In seven years, more than 11,000 goats in 28 villages decorate the hills of Nepal.

With the goat project flourishing, Sitaula wanted to tackle a void in his village that

Sitaula and Russell built a school, fulfilling Sitaula’s dream that all of the children in his village have an opportunity to get an education. Peace flags made by children in Laguna Beach wave on the roofline. had bothered him since he was a boy. While attending boarding school in Kathmandu, he’d wait until the other students had left before he collected pencil stubs and paper scraps they’d tossed away, bringing the discards back home. In a secret spot, he used to share the second-hand school supplies – and his knowledge – with the Dunwar kids, the untouchables, in his village for whom the chance to go to school was merely a dream.

Now an adult, with children of his own, Sitaula was dismayed that there still was no school in his village.

The nearest government school was a dangerous 1-hour walk from Wojethar. Children who made the trek had been abducted by rebel forces and child traffickers or attacked by tigers and venomous snakes. Then there was the $50 annual government tuition, an astronomical fee for many of the families, especially the Dunwars. Those families who could pay the fees – and accept the risks of sending their children out of the village – almost always opted to send a son to school and rarely, if ever, a daughter.

Students at the newly opened “Top of the World School – Nepal” who for the first time have the opportunity to go school, regardless of income, caste or gender. Pooling their own money, Russell and Sitaula decided to make a safe place for every village child, regardless of gender, caste or income, to attend school. It took two years. All the building materials had to be hand carried on a narrow trail, nearly a mile from the nearest road. Long lines of villagers hauled water from the river. And in May 2010, in that “secret spot,” where Situala once taught less fortunate village kids, Wojethar’s “Top of the World School – Nepal,” opened to all of the village’s children. Girls’ tuition is waived and the tuition for boys, whose sisters attend class, is half price, still less than the government charges.

Sitaula and Russell are anxious to build another school in another village where the need is even more extreme.

Up a mountain, on a road more suitable to foot and animal traffic, our taxi lurched. Seeing the approaching vehicle, villagers of Bhedabari raced from their rice fields to talk about their vision. In the shade of two ancient, expansive trees, the chiseled, bronze faced men and women explained how their children must walk 6 hours roundtrip to the nearest government school, a journey wrought with the same perils: kidnappings and tiger attacks. Parents, who can afford it, send their children to a boarding school. The young students don’t see their families for months at a time and wail when they are left.

One of the villagers, Shiva, the village’s mayor, had been to India. Seeing the development there, he realized how backward his homeland is, concluding that education is the key to move Nepal forward. To Russell and Situala, who had already brought them goats, the village elders proposed the idea of building a school. The people of Bhedabari have donated the land, a rolling meadow beneath the ancient trees and they have committed to providing the necessary labor. School plans have been engineered and necessary documentation has been filed with the government. All that is needed now is money.

As she threads her way through the legal challenges that she is hopeful will result in her home being rebuilt, Russell is soliciting funds for the school in Bhedabari, through grants and individual donations.

Meanwhile gifts of goats continue to be exchanged from village to village, women who never had the chance to go to school or start a business are learning to read and are making money. And the lower caste children in one village, who have known nothing but illiteracy and war, are not only learning to read and write, but are receiving 20 minute daily lessons on how to live peacefully in the world – part of Russell’s signature peace curriculum – all in a school less than five minutes from their homes.

“We had nothing in our mind that we’d be doing this,” Situala said. Our plan was no plan. We are learning by doing it and still there’s quite a bit to learn.”

Donations for the new school project in Bhedabari – or for goats – can be sent to The R Star Ministries, P.O. Box 4183, Laguna Beach, CA. 92652. More information can be found on the non-profit’s website at www.rstarministries or by calling (949) 497-4911.

WOW! Reverend! You are and have always been my hero! This is magnificent. The things you have done for this planet. You are so blessed by humility and unconditional love for others. You’re awesome. Very moving article. Love always,

Venesa Talor

Inspiring article!! Bara and I feel so strongly about Rosalind’s work that we have held musical fundraisers to help her cause and participated in events organized by others. It is utterly and karmically WRONG that Rosalind is having to struggle financially to live in Laguna when she does so much RIGHT with the world.