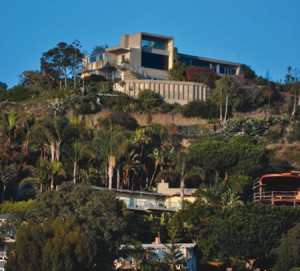

Trying to find the balance between a homeowner’s prerogative and historic preservation, the City Council in a special meeting Wednesday voted 3-2 to ultimately lift a controversial stop-work order imposed the week before on the iconic Halliburton House in South Laguna. On one condition.

Remodeling work will recommence on the famed Hangover House, once home to adventurer and author Richard Halliburton, when the new owner presents more detail on plans to change the house, particularly on changes that have already been made. City building officials found that plans submitted by new owner Mark Fudge didn’t cover some of the specifics of what has already been demolished under an approved city permit.

“We agree that more detail is needed before the stop work-order could be lifted so that there is no question what is and what is not to be done,” said City Manager John Pietig.

The plans omitted detail about demolishing interior walls, said Community Development Director John Montgomery. “They did not indicate which interior walls, specifically for the bedroom closets and the bathrooms, that were going to be demolished,” Montgomery said.

“If they want to demolish or remove any other items in the interior, they also need to indicate that to us,” said Montgomery. The crux of the controversy concerns California Environmental Quality Act regulations as well as existing city rules regarding historic structures and interior changes, which, said Montgomery, do not require a historic preservation report.

The concrete-steel-and-glass Halliburton House, considered an example of design innovation in the history of California Modern architecture, is on the city’s Historic Resources Inventory with the highest “exceptional” rating, but is not listed on the city’s Historic Register. Nor is it covered under the state’s Mills Act, which forgives owner’s property taxes as an incentive to preserve historic structures. A concern was whether the house’s owner could sue the city over personal privacy invasion if he was required to take his remodeling plans, particularly of the interior bedrooms and bathroom, through CEQA as well as city design and historic review, according to a staff analysis.

The staff report cites a lawsuit where a homeowner sued the city and county of San Francisco. The court held that, even though a city holds wide discretion in granting building permits, it cannot require a property owner changing interior walls in an historic house to incur the additional cost of CEQA review.

“What a homeowner plans to do to the private interior of his or her home does not implicate a significant adverse effect on the environment, which is predicate for requiring CEQA review by a municipality,” the court’s ruling stated. The court’s opinion continued by stating that what “may strike some as cultural vandalism will not bring it within the ambit of CEQA unless there is a physical impact on the environment.

“Destruction of an irreplaceable antiquity not being savored by the public does not qualify as a significant effect. We can scarcely believe the Legislature envisaged turning local agencies into censors of homeowners’ plans for interior decoration,” the court ruling continues, acknowledging that historical preservation is a “passionate” issue.

In a letter to the council on Tuesday, Irvine’s Alan Hess, an architectural historian and author, disputes the court ruling. “The exquisite integration of interior and exterior into one unified piece of architecture is a characteristic which constitutes the Halliburton house’s significance as historical architecture,” Hess’s letter stated. “Any alterations or remodeling should take this character into account – if the house’s significance is not to be diminished or lost.”

The council required Fudge to also provide detailed plans for exterior changes before the stop-work order will be lifted. His earlier submitted plans called for: “Repair age-damaged concrete. Demolish and replace interior slab on grade. Repair damaged floor beam.”

The absence of the word “restoration” in the city’s report drew concern from dissenting council members Verna Rollinger and Toni Iseman as well as local residents challenging the city’s position to release the stop-work order before historic review is conducted.

“I listened to the staff report and I heard words like rehab and reconstruct; I did not hear the word restore,” said resident Arnold Hano. “It is absolutely necessary in a case like this that any work that is done has to end up with restoration of this historic house. Without that we have lost a gem in this city and we cannot afford to do that.”

Landscape architect Ann Christoph, a champion of historical preservation, said the key word is demolition. “Demolition requires CEQA (review) under our ordinances,” she argued. “For staff to say, ‘Oh, it’s not very much demolition so, therefore, it doesn’t require CEQA,’ is a completely arbitrary decision. Demolition is on the interior; however, it affects the exterior. It’s clear that we can’t mess up this process again.”

Rollinger concurred. “When I heard John (Montgomery) say rehab and reconstruct in-kind, my heart stopped,” she commented. “What I think we have here are homeowners and a community who want to preserve and restore this property.

“I am distressed by how adversarial our process is. I don’t think there’s anyone in this room who wants to either have this house destroyed or to have it restored in a way that doesn’t meet the needs of the new homeowners.” Rollinger said she would like to see the house restored to remain eligible for the National Historic Register and also meet modern needs.

Gregg Abel, local designer and contractor, commended Fudge on a major undertaking, calling the existing remodeled kitchen the worst piece of architecture he’s ever seen. “I applaud this man and his wife for taking it on. For the most part, it’s really falling apart. That thing has sat there derelict for so many years. Has anybody in South Laguna gone in there to fix it up? Has anybody got the money who’s sitting here complaining? No.” Fudge bought the house last year for $2.4 million.

Other residents were concerned that strict restoration regulations would scare off potential buyers of historic properties requiring work.