After a monumental die-off of millions of adult sea stars from Alaska to Baja California over the last year, scientists on the Central California coast are now seeing a massive influx of baby sea stars.

The “reproduction bout” may spring up in Southern California waters soon, said UC Santa Cruz marine biology professor Pete Raimondi, who heads the Pacific Rocky Intertidal Monitoring Program.

The possible reason for the abundant offspring, Raimondi explained, is because millions of adult sea stars recently disintegrated along the Pacific coast, victims of a still mysterious wasting syndrome. Sea stars that exhibit lesions within hours seemingly deflate and fall apart in the water, a phenomenon spotted in Laguna Beach’s tidepools earlier this spring.

“A lot of animals reproduce when they get stressed,” Raimondi said. “It’s possible, perhaps, that here has been a stress-related reproduction bout. You start seeing them (baby sea stars) nine months to a year later.”

More thumbnail-size sea stars are showing up in Central California ocean waters than have been documented in 20 years, he said in an interview this week.

One of those places includes Terrace Point tidepools, below the UC Santa Cruz Long Marine Lab. Raimondi said scientists documented more than 200 in a cluster. With the first reports coming from Bodega Bay and then San Francisco, other clusters in central and northern California have been cited as well as along the Washington coastline, he said.

An influx of new sea stars could show up in the southern California within weeks. “It could easily occur,” Raimondi said. “It might be a little bit later because the die-off started later down there.”

The epidemic was first noted by scientists last fall and wiped out the usually hearty species from Kayak Island in Alaska to the Coronado Islands off Baja California in less than eight months.

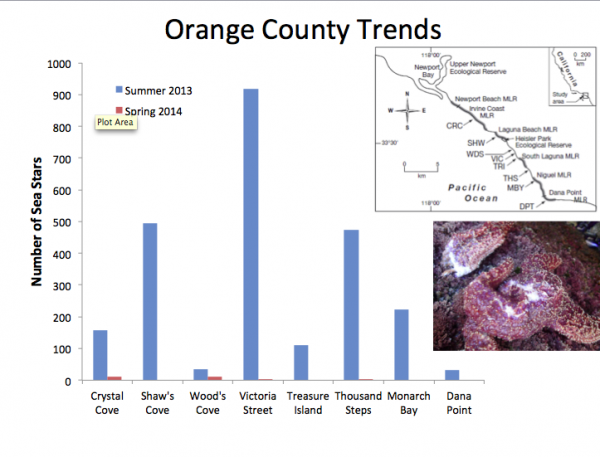

The die-off is being monitored in Southern California tidepools by Jayson Smith, assistant biology professor at Cal Poly Pomona. “I’m hopeful that we’ll see the same thing down here,” Smith said. “We just haven’t seen it yet.” Teams were out this week.

The resurgence of baby sea stars, Raimondi and Smith concur, could be a sign of the species making a comeback or as a “sort of a last-ditch effort to reproduce,” as Smith described the situation. Unfortunately, some of the baby sea stars are also exhibiting signs of the syndrome, Raimondi said.

There have been sightings of new sea-star life in Dana Point, said Sean Vogt, the city’s natural resources protection officer. “There’s definitely sea star larva out in the plankton,” he said. “How fast or when the recovery occurs in Southern California is unknown.”

As part of the monitoring program, Raimondi and his team of scientists along the coast have sent data about the sea star die-off to Ian Hewson, assistant professor in microbiology at New York’s Cornell University. Hewson is overseeing experiments at UCSC and the University of Washington to establish the cause of the devastating wasting syndrome, which he believes resulted from a bacteria, virus or parasite.

Sea stars are broadcast spawners, which means they send eggs from the females and sperm from the males into the water where they mix and fertilize. The fertilized egg larva drift in after about 45 days, and attach to rocky reefs and tidepools, said Raimondi. Mottled first and then becoming a purplish color, it takes six months to a year before they are large enough to spot.

The recent historic mortality event wiped out 95 percent of predominantly ochre sea stars, said Smith. The die-off is unusual because it occurred during cold water. Lesser die-offs have previously occurred during the warm-water upwelling of El Nino conditions, scientists say.

[…] been reported this week that in some of the places where sea star wasting syndrome has recently wiped out the […]

[…] dying sea stars also released sperm and eggs into the ocean to spawn a new generation, noted a report from UC Santa Cruz’s Long Marine Lab earlier this year. The […]