Fifty endangered Pacific pocket mice raised in captivity in the hopes of saving the species from extinction were released into the Laguna Coast Wilderness Park this week.

At dusk, a team of seven biologists opened acclimation cages, man-made underground nest chambers and burrows where the animals spent the previous week adjusting to life in Laguna Beach. The hope of scientists involved in the nearly $1 million recovery program is to re-establish a fourth wild population of Pacific pocket mice in coastal Southern California, where the rodent has been squeezed out of its historic range.

During a press conference at the Nix Nature Center in Laguna Canyon, representatives from OC Parks, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and San Diego Zoo Global provided details about the latest phase of a Pacific pocket mouse recovery program.

The species is critical to the ecosystem because they are seed-eaters that disperse the seeds of native plants throughout their habitat, according to Debra Shier, associate director of applied animal ecology for the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. They also dig burrows that hydrate and increase nutrients in the soil, which encourages growth of native plants, she said.

The species is critical to the ecosystem because they are seed-eaters that disperse the seeds of native plants throughout their habitat, according to Debra Shier, associate director of applied animal ecology for the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. They also dig burrows that hydrate and increase nutrients in the soil, which encourages growth of native plants, she said.

The rodents get their name from external cheek pouches in which they carry seeds, said zoo spokeswoman Jenny Mehlow, who watched at 7:45 p.m. Monday, June 13, as the zoo-bred mice fled their cages for the protection of bushes and began foraging for seeds as if they were native-born park dwellers.

The tagged mice will continue to be monitored by zoo scientists, who will return to trap them and check on their health.

“This is an experiment to see if the habitat will support them,” said Ileene Anderson, a scientist from the Center for Biological Diversity, which petitioned the U.S. Interior Department with other conservation groups in 2000 to map out and protect critical habitat areas for the pocket mouse.

Captive breeding programs for endangered animals, such as similar efforts undertaken for the California condor and bald eagle, remain exceptional, resource intensive efforts undertaken only for species in dire peril, Anderson said. “It’s much better to save the habitat and keep them in the wild,” she said, though pointing out how human intervention succeeded with bald eagles, which are no longer endangered.

Four years earlier, Pacific pocket mice were captured for a breeding program from three remaining wild populations in the region, two areas in Camp Pendleton and in the 22-acre Dana Point Headlands preserve. The mouse was detected in an environmental survey in 1994 for a proposed resort, still unbuilt, on the Headlands that overlook Dana Point Harbor.

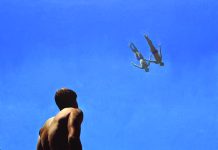

To help ensure their survival in the wild, the 50 pocket mice released in the county park went through predator aversion training. Training consisted of playing a recorded warning screech by a Pacific pocket mouse when captive mice were exposed to a caged snake. A taxidermy owl on a zip line was used to acclimate the mice to the overhead threat of an owl in the wild. “If they didn’t show they were retracting, they didn’t make the cut,” said Mehlow, referring to a few rejected release candidates retained for breeding. About 100 animals remain in the breeding facility

A small microchip under the skin of the released animals will allow biologists to identify each and track their health information.

Summer is midway through the March to September breeding season for the Pacific pocket mouse, and some of the 50 released animals are expected to raise pups in their burrows, the scientists say. The gestation period is 23 days.

“We are honored to welcome the Pacific pocket mouse back into its historic range, in the Laguna Coast Wilderness Park,” Barbara Norton, supervising OC Parks ranger, said in a statement.

The Pacific pocket mouse is the smallest rodent species in North America, with adults typically weighing between 6 and 7 grams (about the same as three pennies). The nocturnal species was thought to be extinct in the 1980s, but it was rediscovered in 1993 and listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1994.

The mice were once common up to three miles inland in coastal sage scrub along 142 miles of coastline, between El Segundo dunes and the Mexican border, Mehlow said.

In 1998, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed a $7.5 million recovery plan. “Saving the Pacific pocket mouse from extinction has been accomplished through collaboration with numerous federal, state and local partners,” Michael Long, a service division chief, said in a statement this week.

With habitat shrinking due to development, state and federal wildlife regulators decided the Pacific pocket mouse population couldn’t maintain enough genetic diversity to recover solely in the three remaining wild populations and began talks with zoo scientists, Mehlow said.

The zoo breeding program, part of the wildlife service’s larger recovery program, was supported by private, state and federal grants of more than $800,000, says a statement.

In recent years, the San Diego Zoo Global has also assisted with the re-introduction of the California condor, the mountain yellow-legged frog in San Bernardino, the shrike bird in San Clemente and relocated ground squirrels and burrowing owls, Mehlow said.