My Father In His Turquoise Vinyl Recliner

Swaddled like a mummy, my father lay on his turquoise vinyl recliner, with a second blanket protecting his lap against a chill. It could have been 1951 when he and my mother and their four children crossed the ocean to America as refugees crammed into the hammock-filled holds of the U.S.S. General Muir. We were those huddled masses cited in the Emma Lazarus poem I later memorized in English class. But, in the late spring of the year 2000, we sat in his living room in Skokie, Ill., with the heat turned up high amid the dim light cast by the gilt-shaded table-lamps.

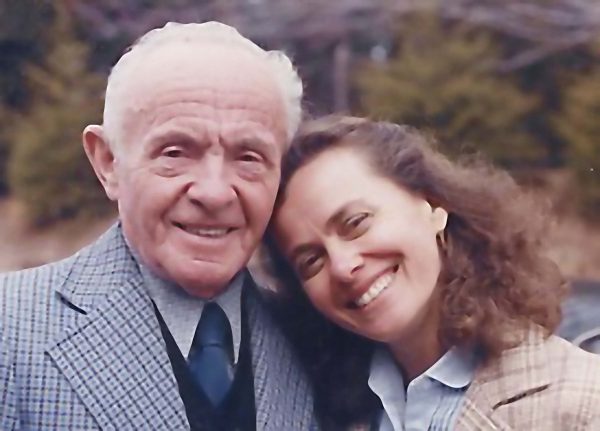

My father’s dear head was cocked toward me, his eyes bright, his entire universe focused on the words I read aloud to him. The broken footrest on the lounger forced his once wiry, now gaunt, body askew, but there was no point in buying a new chair, he insisted. That was not an issue I chose to push.

I read to him about our life according to me. I write memory pieces of an immigrant childhood with no aunts, uncles, cousins or grandparents, and only an evil called Hitler to blame for the annihilation of a world before I was born. It was a world I warmed to from my father’s character-filled tales, peopled with nicknames like Chana Beila, Chaim Tsudik, and Kalte Tuches, but his story-telling came later in my life when the drumbeat of work was less strong.

He listened intently, that day, as I read about life in the backroom of the grocery store he and my mother tended 14 hours a day during my childhood. No labor was too heavy and no hours too long. I described the Sunday afternoon they reopened the just-locked and bolted door for a customer in desperate need of a pint of sour cream. We were about to embark on a rare family outing at Humboldt Park, but after the sour cream lady, another person wandered in and then another – a gallon of milk, a half-pound of sugar wafers, kaiser rolls for tomorrow’s lunch. They dribbled in, the afternoon passed, my father rolled up the awning, and eventually it was too late for the park. My parents closed the store at 11 p.m. as usual.

The cardiologist said my 88-year-old father’s heart function was extremely diminished. He was also near kidney failure, this man who as a boy was so nimble in mind and body that he was honored to study with the highly regarded Gere Rebbe and in off-hours he helped his grandfather repair roofs in their shtetl. As a child I marveled that he knew the siddur, the Jewish prayer book, by heart. Occasionally he glanced at a page, but mainly he davened from his head and his now failing heart at a pace beyond my ability to read along and follow. During his 20s in vibrant Warsaw, he became an ardent Zionist, met the Polish Chief of State Josef Pilsudski in person, and knew both Yiddish literary brothers, Isaac Bashevis and Israel Joshua Singer. He used to tell me that just like him, the respected Singers brothers were so poor, they all had holes in their shoes.

Then in 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland, my father, among others, fled eastward toward Russia. Swept up by the Russian army, he and my mother were deported to Komi SSR, a Siberian labor camp, where they felled trees in the brutal winter. They survived the war, sojourned in a displaced persons camp in Bergen Belsen, and, eventually immigrated to America and Chicago. There, he sold groceries and, later, dry goods, to support the family. He loved nature, progress and technology and figuring out how things work. After his late retirement he audited classes at Oakton Community College. His grandchildren recited a poem at his 70th birthday party that proudly announced, “Zeide goes to college.” He was an avid autodidact, determined to acquire the education he could not get in Poland.

Inclined to be quiet at home and gregarious in company, my father was a man of many aspects. A ballroom dancer, a disc jockey at a senior center, he had a deep knowledge of politics and history. He began kicking a soccer ball with my children when they were barely more than toddlers. He also introduced them to schmaltz herring, which grossed them out, and they introduced him to McDonald’s, which grossed him out. In me, he instilled a love of nature and animals and empathy toward all living creatures. Most particularly, he gifted me with his sense of humor, his intellectual curiosity and an individual view of the world.

I remember reading to him that particular day on one of my last visits. Marina, the kindly nurse who saw him at home each week, observed that he wasn’t having a good day. “Herman,” she said, as she checked the tubing that delivered oxygen into his nose. “You’re accumulating a little fluid in your lungs, but we’re going to fix that and get you all better.”

My father wiped absently at the rawness where life-sustaining plastic met flesh. An impish smile played around his mouth. “Thank you, Marina,” he said. “You know I want to be in perfect health when I die.”

Herman Nuss passed away in his bed in September of 2000. He was proud to have seen the new millennium.

Sara Nuss-Galles, of Laguna Niguel, is a member of Laguna Beach’s Third Street Writers. She has completed a collection of illustrated short stories, “Those Seven Deadly Sins.”

What a lovely story. Thank you for sharing it.

Oh Sara,

It’s so easy to love your father.

I feel he is part of my family.

XO

Ilene/Gingy