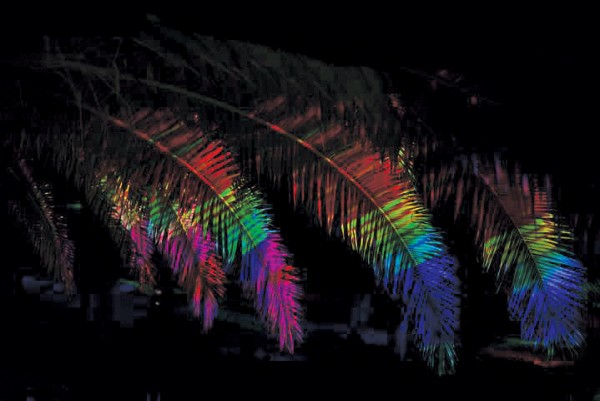

A green beam of light shot along the shore at Main Beach, striking a straight line through the dark water.

As the next wave crested, it broke the beam, shattering the green light like so many shards of dancing glass, reminiscent of phosphorescent tides. It was an eye-popping effect the creators of the show had not expected.

It was the last of two, hour-and-45-minute outdoor light shows Saturday night, and comprised the third installment of the annual Art and Nature festival produced by the Laguna Art Museum. Titled “Electric Light Blanket,” the commissioned outdoor work of art, called temporary land art, was created by acclaimed laser and space artist Laddie John Dill, who collaborated with portrait artist Jack Barnhill and Laserium laserist Jon Robertson, all from Los Angeles.

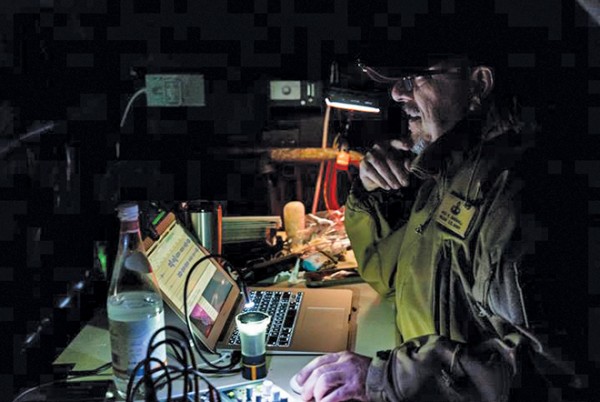

The beam wasn’t supposed to stay at the surf line, said Barnhill. Barnhill was directing the show’s sequences from his laptop in the open-air control booth at the top of a walkway above Main Beach, giving change-cues to Robertson. Robertson, manning the light switches at the control board, had placed the laser beam earlier, not anticipating the changing tides. After the impressive display of light colliding with breaking waves, however, the surprising effect became a mainstay of the show.

The play of the light beam at the surf line wasn’t the only unexpected effect. Hundreds of people milling about on the sand in the middle of geometric and spherical light forms broke up the patterns being projected from the bluff top, becoming impromptu performers in what was becoming improvisational. The interchange of art with nature now included human nature.

It’s not that people weren’t part of the equation, said Dill, just not so many.

Lasers, Dill explained, can be holographic.

“From the cliff, we made these shapes that encased people down on the beach,” he said. “But there were quite a few people Saturday night and that broke up the beams.”

A sea of illuminated cell phones recording the show added another human element and pattern of light to the scene. Some people brought their own LED light toys to spin around; a young woman danced skillfully, sensually and gracefully with a lighted hula hoop.

“What we would do next time,” said Dill, “is make the shapes big enough to encompass more people. I would design it a little better, say, so that you got that holographic feeling and the people were still in the middle of it. It’s a work in progress.”

To some, it was a no-brainer—people were going to gather and interact on the sand, especially in Laguna on a warm November night. To others, it was mildly distracting.

“You’re in the way, people” one young man called out, half-jokingly verbalizing what others were thinking. The show was projected on the sand with an occasional spilling of lights on the undulating sea, a crowd-pleasing juxtaposition of structure and spontaneity.

“I don’t want to discourage people from experiencing it,” said Dill, watching from the control booth as his creation evolved. “It was an interesting experience, especially down by the water. If we do it again, wherever on the planet we do it, it will be more over the water, where the water and the sand meet.”

Nearly 2,000 people came out to experience the two shows, on the beach and from the walkway, said Marinta Skupin, the museum’s curator who helped coordinate the event. “The walkway was jammed,” said Barnhill.

As the show progressed from defined geometric patterns twisting and turning into each other to globular, veiny projections that glowed and undulated like one-cell creatures at the bottom of the sea, even the people’s presence appeared to become more fluid.

“The multi-sensory event stimulated synesthesia where the senses mingled; color became movement and light emotion,” said resident Robert Gluckson, an adjunct professor of photography at Saddleback Community College.

As with most artistic experiments, the process was equal to the content. Dill’s idea, said laserist Robertson, was to present a metaphor using hard graphics contrasted with organic, ever-changing shapes.

The geometric design represented modern society’s infrastructure and grid-like succession of achievements, he said, while the more spatial, nonlinear shapes represented the “lumina” or light-bearing side of nature, as seen in the surf. The surf represented nature as an unpredictable force, “which invariably humbles us and washes us away over time,” he said.

“It was the intersection of the two. We work with nature and nature always works us over. That was the amazing dichotomy of Laddie’s whole performance.”

During the final lumina sequence of eclipsing globes, people down on the beach became less animated and more meditative, giving the projections lava-lamp-like movement, Barnhill observed.

At the first show, which started at 6 p.m., spectators lined the viewing pathway above the beach just as a Navy unarmed test missile from a ballistic submarine shot overhead, launching a bluish-green smear, another unanticipated special effect. “That was more scary than anything,” commented resident Charlotte Masarick.

[…] article “Lasers Light Up Main Beachgoers“, which appeared in the Nov. 13 edition failed to mention the many contributions of artist […]