The young woman is beautiful in the classical manner of ancient Greek statues, pensive with her gaze averted and posed against a calm ocean and cloudless sky. With the light shining through her dress and one foot resting on a stone, the seated figure is painter David Ligare’s version of Penelope. She is the wife of the seafaring Greek hero Ulysses and whose vision of marital fidelity was as strong as Ligare’s adherence to classic beauty and compositional order transposed into the art of modern times.

“I have said over and over, ‘As a society, we are in need of a renewed desire for knowledge.’ Art can answer that need by inspiring us to look at history and the foundational elements of our culture,” artist David Ligare said in a Huffington Post interview. “There were amazing thinkers in ancient times. That rich wisdom seems so radical to me, and it is often totally applicable to contemporary situations,” he said.

Ligare’s Penelope is among the figures included in the current retrospective of his monumental and smaller paintings and drawings at the Laguna Art Museum. “David Ligare: California Classicist,” which will be seen through mid-January, traveled from the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento and is accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue.

Whether he paints figures, still lifes or landscapes, his technical abilities and realistic rendition of them have earned him the label of “realist,” but it is one that falls far short of his talents as historian, story teller and even surrealist, as suggested in his depiction of “Orpheus” and “Arete (Black Figure on a White Horse)” and similar paintings placing unlikely humans or animals into pastoral settings.

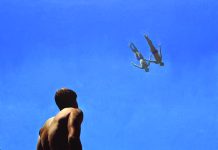

More often than not, his monumental paintings allude to classical philosophy and literature and to his conviction that art should uplift and educate and bring out the best in society. Hence a painting like “Hercules Protecting the Balance between Pleasure and Virtue” where the composition is carefully balanced with Hercules in the center and the women, one clothed the other gowned, holding equal visual sway.

“Achilles and the Body of Patroclus, (The Spoils of War)” is a quasi pietà filled by men filled with grief and bewilderment, a connection between past and present wars, tragedies and loss. Ligare’s mastery of light at once recalls Renaissance masters and 20th century pioneering photographers.

Some may be baffled by depictions of ephemeral floating draperies named after Greek islands, but these, again exquisitely rendered, are meant to be reminders of aesthetically and historically priceless works of art that have been created and lost over time.

Then again, pastoral scenes such as “Grimes Point, Big Sur” and “Landscape with Broad River” reflect the beauty of the Monterey area that the artist calls home. It’s enlightening to contrast their pristine purity with a more fantasy based landscape titled “Landscape for Baucis and Philemon,” which shows a small temple dedicated to the Roman gods Jupiter and Mercury. The story behind it is based on Book VIII of Metamorphoses of the Roman poet Ovid, where an elderly couple befriends the disguised gods on a journey while their fellow townsfolk, perceiving them as vagrants, wanted to run them out of town. In revenge, the gods drown the lot, hence the beautiful lake. So goes the story, as told by Executive Director Malcolm Warner during a recent tour.

A standout by any standard is the painting titled “Rocks.” Here, a meticulously rendered large rock is surrounded by a landscape of countless, equally compulsively detailed stones reaches to the horizon, suggesting the ocean and infinity beyond. It’s a painting that one is not likely to forget anytime soon.

Also remarkable in their execution, composition and detail are Ligare’s still-lifes such as “The Philosophy of Flowers,” and drawings like “Two Shells,” found in the museum’s upper gallery.

Throughout the exhibition, some might find some of the male figures a bit too idealized and female depictions given short shrift, but then such were the ways of classical epochs. Altogether, the show illuminates the work of a California artist working since he left the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in 1965 and has yet to become a household word. Yet, as the small exhibition at LCAD attests, he might well serve as a role model for generations to come.

[…] with magic (“Florine, Child of the Air,” “Portrait of Queen Zozer II”) as well as David Ligare’s meticulous drawings (“Thrown Drapery,” “Sand Drawing”) that were seen here in a major 2015 […]