Diving 50 feet to the ocean floor off Laguna Beach’s coast was like landing on a desolate, evacuated planet. There was no sign of life. Not even a lone, drifting kelp spore or a tenacious purple spiny sea urchin to devour it.

“When we started, there was nothing there, nothing,” said marine biologist Mike Curtis. In 2002, Curtis led a small team of divers under a $500,000 contract and replanted 25 acres of kelp over nine years. “We started putting kelp in and immediately, immediately, we started seeing more fish,” said Curtis, a consultant at Costa Mesa’s MBC Applied Environmental Sciences, specializes in marine monitoring, ocean restoration and remediation cases. The funds for this project came from an aerospace company cited by regulators for washing toxins into the sea.

The kelp beds in Laguna now number 100 acres. Putting on his wetsuit and dive gear, Curtis surveyed the beds last week. “Oh my god, it was beautiful,” he said, describing purple kelp shoots, a color that indicates robust kelp health.

But prickly purple sea urchins, which eat kelp, are plentiful, too, and a point of contention with another scientist key to the project, who’s prickly herself about newly imposed marine restrictions that prohibit human intervention, including her efforts to remove them.

Marine biologist Nancy Caruso also raised money to replant kelp in Laguna. To prepare the selected reefs, she and 250 volunteers removed up to 1 million sea urchins that had overpopulated kelp reefs, eating them bare. The team picked urchins off reefs and rocks by hand, piling them into a boat and relocating them to deeper water.

Then both Curtis and his divers and Caruso and hers attached the kelp’s roots, known as holdfasts, with wide rubber bands to the rocky ocean floor. Offshore Main Beach was one of the first places replanted, which became part of a Marine Protection Area in 2012 that made fishing, along with removing any ocean plant or animal, illegal nearly citywide.

Caruso asserted that urchins still pose a threat to the kelp forests. She continued diving at Shaw’s Cove and Crescent Bay, removing urchins off the reefs as usual, when Department of Fish and Wildlife officials told her to stop; her actions now violated state marine protections. She had re-applied for an annual permit, which was denied.

“We’re currently not permitting any urchin removal in those Marine Protected Areas,” stated Rebecca Flores-Miller, an environmental scientist with the state Department of Fish and Wildlife in Monterey.

“The spot I was restoring, that whole area of Crescent Bay and Shaw’s Cove, still has too many sea urchins in it,” countered Caruso. “There shouldn’t be masses of them. They should be dispersed at low density.”

Caruso said she is still aggravated with Fish and Wildlife officials for recently permitting the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Foundation to smash urchins blanketing the reefs off the Palos Verdes peninsula. “The work they are doing at Palos Verde is not in an MPA,” explained Flores-Miller. “It just involves purple urchins. And they’re also doing extensive monitoring and reporting.”

Kelp beds off Laguna are also being monitored regularly and regulators review reports every five years to determine whether the MPA should remain or change, Flores-Miller said. The conservation measures allow marine ecosystems to restore and recover as naturally as possible. With kelp, that means the return of the keystone predators to keep the urchin populations in check, Flores-Miller said. Healthy kelp beds bring keystone species like lobsters, sheephead and even the extricated otter to feed on urchins.

Caruso and Curtis agree that the kelp forests are flourishing, and luring back an array of wildlife. But Curtis takes exception to Caruso’s anti-urchin crusade. Urchins, he said, aren’t gluttonous.

When there’s enough kelp, fallen kelp leaves satisfy urchins’ appetites. When there is not enough kelp, urchins become ravenous for any bit they can get, including any little kelp spore that happens by, which prevents the kelp from regrowing. “There’s lots of kelp out there so the urchins are fat and happy and sassy,” said Curtis. Although urchins will admittedly eat a reef barren, he asserts they won’t when there’s enough kelp to go around.

But Caruso thinks that could be temporary. “As long as the kelp’s doing okay it will keep the urchins satiated, no problem,” she said. “But if we were to have a catastrophic event, like another El Nino, that could wipe out the kelp beds.”

In the early 1990s, a series of warm El Nino ocean currents swept north to typically cooler ocean habitats. The warmer water killed nutrients needed for marine animal and plant life, which subsequently killed a lot of marine animals and plants. “All of a sudden, the kelp disappeared,” explained Caruso. Another El Nino, she said, could easily tip the balance. “All of a sudden, those urchins are going to get hungry and then they just eat everything that starts growing.”

Transplanting kelp is not all it’s cracked up to be, said Curtis. It takes more luck than labor. “Transplanting never brings back the kelp,” he said. “All it does is it puts the seed source out there. You just need to wait until the environmental conditions get right and then nature takes over. But if there’s no kelp there and the conditions are right, nothing happens.” Curtis said his team planted about 1,000 kelp plants at two depths, evenly split, just in case El Nino comes ‘round again. One depth was about 25 feet, the other and colder, 50 feet plus.

Even when high surf and strong tides pull kelp to shore in smelly piles and people start complaining, “there’s never too much kelp,” he said. “That’s the normal course of things. It’ll come and it will go.” Curtis has survey records dating back 50 years and said the amount of kelp bobbing offshore now is normal. “It’s actually way down from what it was in 1911 when they did the very first survey,” he said.

Photos:

Biologist Mike Curtis measuring kelp plants per acre off Cleo Street in Laguna Beach last week.

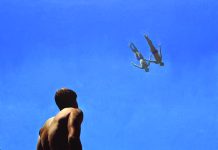

Underwater kelp forests off Laguna’s coastline.

Biologist Nancy Caruso with kelp-munching urchins in Shaw’s Cove two years ago.

[…] biologist Nancy Caruso, the festival is a community based celebration of kelp, which is enjoying a resurgence in the waters off Laguna, where it shelters a growing abundance of […]

[…] imposed marine restrictions that prohibit human intervention, including her efforts to remove them…..Then both Curtis and his divers and Caruso and hers attached the kelp’s roots, known as holdfasts, […]

[…] said marine biologist Mike Curtis. Curtis and his team from MBC Applied Environmental Sciences planted 25 acres of kelp along the Laguna Beach coastline in 2002 that burgeoned to more than 100 acres, he […]