It takes passion to launch a non-profit organization and resources to sustain it. Wossene Bowler, a Laguna Beach resident since 1996 who is the founder of Life’s Second Chance Foundation, is long on passion, but short on resources.

She does possess a reservoir of good luck and determination.

A cancer survivor, Bowler, at 52, is determined to make her new lease on life count by building a cancer referral hospital in her native Ethiopia. One expert described a cancer diagnosis there as akin to a death sentence because of the nation’s scarcity of resources.

Driven to succeed, Bowler has already convinced about 500 people in the town of Sheno, about 36 miles north of Addis Ababa, the country’s capital, to contribute 68 hectares of land to build a hospital and the government accepted the transfer of ownership.

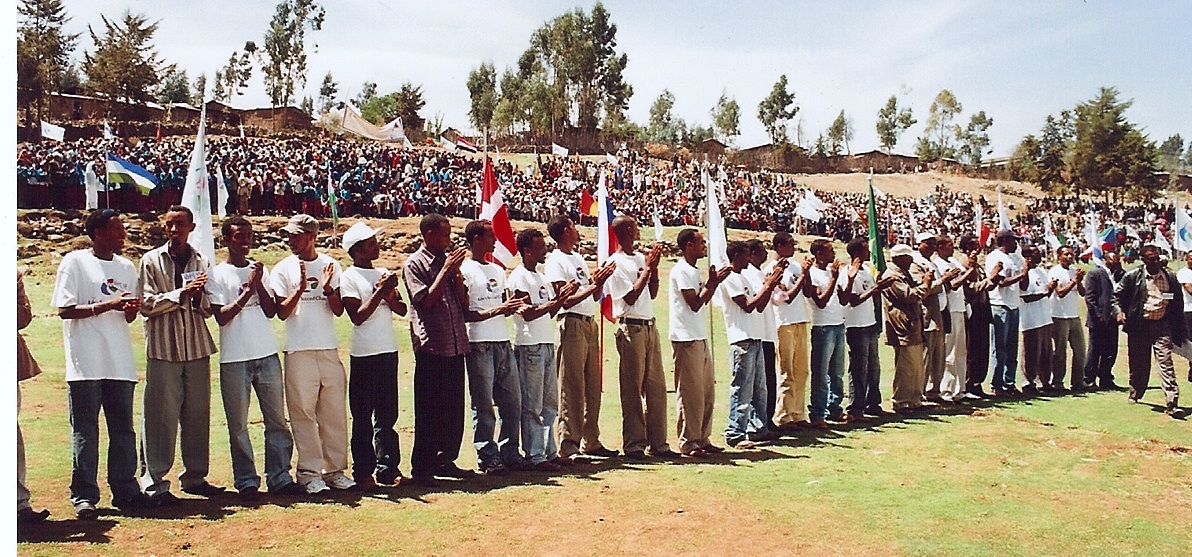

Bowler also founded a local committee of youth volunteers. She hopes to eventually pay as many locals as possible as employees that would build and then staff the hospital. She says that the volunteers who help her in Ethiopia “work out of hope. I give them hope.”

LSCF has land, a site plan and a business plan, but to become viable, Bowler recognizes she needs much more, including hands on directors, an office, administrative support and a fundraising arm. Passion alone won’t sustain a project starved for capital. “With a little money, I took it so far,” said Bowler, who estimates the hospital’s construction cost at $134 million.

Steven Wozencraft, a Laguna Beach resident and member of South Coast Medical Foundation’s board, may be able to help.

Wozencraft is the president of New York-based John O’Donnell Company, which specializes in financial development for non-profit organizations, and has volunteered to help Bowler. “I think there is tremendous potential for her,” he said.

The need is clear. “There are only three medical oncologists in the entire country, one radiation therapy unit, and no pediatric oncologists,” explained Patricia Hoge, an American Cancer Society official. “Thus it is impossible to treat early cancers. There are just no resources for early detection and if detected early, no resources to be able to treat it.”

Dr. Bogale Solomon, an oncologist at Tikur Anbesa hospital in Addis Ababa, which has the only cancer unit in the country, agrees. “Public awareness of cancer is very low and the diagnosis of cancer is considered a death sentence,” he said. “The waiting time, particularly for radio therapy is six months. As a result, some patients die while waiting for treatment.”

Bowler emigrated from Ethiopia in 1980 after her father was killed when the communist regime came to power in 1974. The family was stripped of its possessions and became a target of the government. Bowler made it to the United State, but her siblings remained behind and one of her brothers was eventually taken into custody as a political prisoner.

In 2000, Bowler was diagnosed in the United States with CML leukemia after a routine blood test for an unrelated issue. She was lucky doctors detected the disease so early. Her luck held further when she needed a bone marrow transplant, which her brother could provide, the same brother who had been imprisoned.

Her sibling might not have been around if Bowler hadn’t pulled strings to get him released and persuaded him to immigrate to California, little realizing the future role he would play in her life.

During a return trip to her homeland after her recovery, Bowler came away overwhelmed by the lack of resources for cancer victims. Suddenly, her mission was clear. “God saved me for a reason,” she said.

Bowler’s husband, Dennis, who owns a pet treat company, Full Petential, gave her $10,000 to start Life’s Second Chance Foundation, which received nonprofit status in the U.S. in 2006, and in Ethiopia. She’s applied for similar registration in Canada and the United Kingdom.

Bowler’s vision is to equip and furnish Ethiopia’s first-ever cancer care and research training center with the most up-to-date medical equipment, and to fight cancer on four fronts: patient services, research, education, and advocacy.

LSCF sponsored a cancer awareness conference in Addis Ababa last December. Part of its purpose was to introduce the American Cancer Society to the local community. During the event, Hoge awarded Bowler a survivor medal.

Until the hospital becomes a reality, LSCF aims to provide equipment and medication to Tikur Anbessa hospital to offer immediate help to current sufferers. Last September, the foundation supplied the hospital with incubators, mammogram equipment and medical supplies.

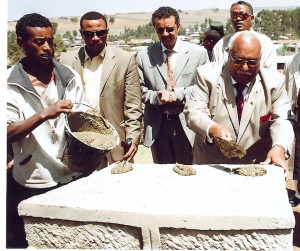

The Ethiopian government strongly supports Bowler’s project, and Ethiopian president Girma Wolde-Giorgis participated in the groundbreaking ceremony for the hospital on May 10.

But cancer does not top the government’s funding priorities. Limited resources fight HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Dr. Medhin Zewdu Tschaiu, a special assistant to Ethiopia’s health minister, told Hoge at the awareness conference that the government fully supports Bowler’s initiative, but lacks the resources for what it recognizes is its rightful responsibility.

The “idea of establishing a cancer hospital is a noble one as there is an absolute need for such an establishment in Ethiopia, a country with 80 million people,” said Awash Teklehaimanot, a clinical epidemiology professor at Columbia University, who is the director of the Center for National Health Development in Ethiopia. Teklehaimanot works with the United Nations’ Millennium Project, helping underdeveloped countries reach goals such as reducing hunger, providing primary education, disease control and environmental rehabilitation. He said their resources are too limited to support Bowler’s project, which he praised for including local people and local institutions.

Wozencraft, too, is impressed by Bowler’s incredible drive, but says LSCF needs infrastructure to woo established non-profits and larger organizations. He suggested finding people who already have an interest or a personal connection in the area, adding that he has a connection at the World Health Organization who might offer a potential lead. “At the end of the day you’ve got to be able to show them that you can use their help in a way that will be fruitful.”

For more information about Life’s Second Chance Foundation, visit www.lifessecondchance.org.