The decade following World War II turned into golden one for artists and specifically for emerging photographers, spurred on in their ambitions by the pioneering photography of Ansel Adams. He served as a role model and teacher for the young men and a smattering of women who vied to attend the California School of Fine Arts between 1945 and 1955.

Adams founded the school, later renamed the San Francisco Art Institute, in 1945 and hired contemporary Minor White to chair its photography department. Other notables including Adam’s friend Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, Edward Weston and Lisette Model joined as faculty.

Photographs made during that decade at the San Francisco school form the core of the current Laguna Art Museum exhibition “The Golden Decade: Photography at the California School of Fine Arts, 1945-55.”

The exhibition is based on a recently published coffee table book by the same title. It is curated by photographers Ken and Victoria Whyte Ball and John Upton and the museum’s executive director Malcolm Warner. The couple edited the book.

Given the number or photographs, many of them platinum prints made with large format cameras, the show is worth more than just one visit.

Evidently the above mentioned masters whose work is also represented here taught their students well. For example, Dorothea Lange’s photographs of Depression-era field workers illustrate hardscrabble lives of migrant workers, mostly Caucasian at the time, and also resilience and a will to survive. (White Angel Breadline, San Francisco,” 1932” and “Homeless Family, Oklahoma,” 1938.) White is represented by the dramatic “Point Lobos,” 1948 and Adams by “Yosemite Falls,” 1947 and others. And then there’s Weston, whose contact prints were made minus an enlarger. Note one of his famously sensuous peppers.

Cunningham (“My Father at 90” 1936) made it her mission to mentor the few women students, such as Pat Harris. Her 1950 photograph juxtaposing a freestanding white townhouse against a dark industrial structure stands out as a simple but dramatic composition. (“San Francisco” 1950)

Lee Blodget’s image of a rusty wreck of a car before a dilapidated cabin underscores prevailing economic conditions in a region that now counts itself among the wealthiest in the nation.

The same holds for Eliot Finkel’s “Boots,” and Blodget’s beautifully composed shot of workers stringing electric wire in “California, c 1948.” Work then was as hard to do as it was to get.

What adds to the show’s appeal is that audiences get a chance not just to see beautifully composed and crafted photographs, but also a taste of history.

Joe Humphreys’ shot of two nuns in full habits, rarely seen today, stands out. We can deduce from the women’s joyous expression that they not only enjoyed their lifestyle but the prevailing art of the time.

David Johnson, the only African American photographer here, trained his lens on his own, then segregated community. Reportedly he wrote Adams, requesting admission to CSFA and found it prudent to mention that he was a “Negro.” Adams wrote back that it made no difference and found him a spot.

Johnson’s “Dancing in the Joint in the Bayview District,” evokes sounds of jazz and laughter, and his street shot taken in the Fillmore District has an energetic vibe and yes, parking was a bear even then. Geraldo Ratto found similar inspiration in the neighborhood that shows refreshing ethnic diversity, and George Wallace’s shot “Laughing Boys” also falls into that category.

So what was it that made the decade so important for artists and photographers? Droves of young soldiers returned from serving in the Pacific theater and Europe during World War II. They were eager to re-integrate themselves into civilian society by learning new skills and occupations. To help them, Congress passed the GI Bill in 1944, giving them education and other economic benefits. The downside was, as Harris states in her book bio, few were women vets. Women students such as she, had to work their way through school, often married and employed at the same time.

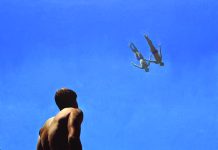

But, as photographs by Charles Wong attest, the young men were ready to embrace multiple benefits of state-side life. “Friendly Fire,” 1951 shows two sailors trying to chat up two young women who are not exactly eager to join them. “Untitled” 1950s shows that at least one soldier or marine had better luck.

Altogether, this well-edited show offers visual fare and food for thought to seasoned photographers and those new to the medium. With all works in black and white, it’s also a welcome change from a color-saturated world. What’s more, the book offers yet more than the show: With spare use of technical jargon, save for descriptions of the masters’ innovations, such as the Zone System, it offers insight into the lives of the students, many of whom went on to become “names” themselves.

One hopes that the museum will continue to provide a platform for photography as an art form and a means of serious communication in an age of smartphones and selfie-sticks.

[…] Read the article online here. […]

[…] Read the article online here. […]