Salt Fine Art’s ¡Cuba! exhibition, featuring multi-media works imbued with sly political commentary by 11 artists, opened early this month with something missing: most the artists were absent.

Part of gallery owner Carla Tesak Arzente’s planning included making arrangements to host the artists from Cuba. But no thanks to Cuban bureaucracy, only Ernesto Javier Fernandez and his gallerist wife and co-curator of the show, Sandra Contreras, received their visas in time to attend the reception in their honor during January’s First Thursday Art Walk.

After nearly 60 years since Castro came to power, getting out of Cuba is still a herculean enterprise.

“Artists, unlike regular residents, get exit visas since Fidel has been eager to show off Cuba’s talent, but it is still a process that is no more transparent than trying to gauge the mood of whoever’s handling the application,” said Fernandez.

A photojournalist and art photographer who has lived and worked in the former Communist-controlled East Germany as well as West Germany, said his relative freedom entailed sacrifice. “I was allowed out but never with my family. Even though I spent altogether eight years in Germany, I went back because I missed my daughter,” he said.

Other artists featured in the exhibit, husband and wife William Perez and Marlys Fuegos, and Alejandro Campins, finally received their visas days after their colleagues’ departure. Arzente is scheduling a second opening on Feb. 2 on their behalf.

“It was nerve-wracking counting the days and hours until their arrival,” said Laguna residents Karen Redding who, with her husband Ed Kaufman planned to host Perez and Fuegos in their home. “We wanted everything to be ready for them. We had enough food to feed an army,” said Redding, who expressed disappointment but nevertheless attended the show’s opening. “We felt that their spirit was there,” she said, now delighted that they will still serve as hosts.

Carla Arzente and her husband George hosted Fernandez and Contreras at their home.

In expat enclaves such as Miami, scores of native Cubans without the appetite for a Communist-ruled “worker’s paradise,” have fled across the Florida Straits by any means available.

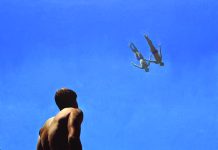

Known colloquially as balseros for the jerry-rigged wooden crafts many use for the journey, they risk 20 years in prison for trying to escape if caught or worse, drowning.

One of the most striking images in the exhibit is a 1994 Fernandez photograph of a ragtag flotilla titled “Ideas,” which attests to the dangers of crowding too many onto what often is little more than a raft powered by a small sail. “Ideas” contains the Spanish word ide, to depart, as well as suggesting the hunger for intellectual freedom, explained Fernandez, who juxtaposes neon signage into his photos.

Another titled “Wash Your Hands” attests to the sense of irony inherent among people forced to maneuver by their wits through the most mundane aspects of daily life. The photo depicts what was once Havana’s most fashionable

thoroughfare in a ruin of rubble off-set by the neon admonition for cleanliness.

Soap, says Arzente, is difficult to come by. So is evidence of rebuilding in Havana, where the regime permits little construction and the built landscape remains stuck in 1959.

Esterio Segura’s pieces, “History of An Old Fisherman” and “Enjoying Ideology,” are, like nearly all other works exhibited, rife with innuendo and satire. The former consists of a bright orange, roughly three-foot sculpture of Pinocchio imprisoned in a birdcage. The little liar’s telltale nose balances a life-size fishing pole dangling a tiny fish with a sickle lure in its mouth. The boy’s hands, clasped behind his back and cradling a hammer, underscore the artist’s take on the reality of life under Communism.

“Enjoying Ideology” is a linear wall sculpture suggesting a couple engaged in carnal knowledge or, in the vernacular, doing what Castro has done to Cuba, explained Arzente during a gallery walk-through. Pinocchio, prized at $30,000, has already attracted strong collector interest. His fiberglass compadres are in demand by museums and galleries throughout North America and Europe but are banned in Cuba, she added.

It’s also noteworthy that artists that sell works here, cannot repatriate their earnings. Since they also cannot maintain U.S. bank accounts, many establish accounts oversees, administered by trusted friends.

Anything beyond their state-mandated salaries is confiscated, confided Fernandez, 48, who opened a print shop when Castro began to allow small businesses and just recently received permission to purchase a used car.

“Everyone has a day job. Art is to have fun,” he said.