By Robin Pierson, Special to the Independent

How does a mother, and a self-described worrier, watch her cancer stricken son walk off alone into the wilderness without plunging into a pit of anxiety and fear?

She works at it.

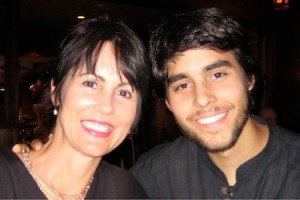

By looking unflinchingly at the reality of her son’s illness, fully feeling the accompanying emotions – the grief and the trepidation – then letting them go – Laguna Beach’s Betsy Gosselin has learned to live beside her son’s cancer and to live well.

When her 23-year-old son, Andy Lyon, decided to hike the 2,660 mile Pacific Crest Trail after the best Western medicine had to offer failed to eradicate his Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Gosselin embarked upon her own equally arduous journey, an exploration of her own mind.

A seasoned meditator with a daily practice, Gosselin began to realize and absorb the truth that “I’m not the only mother of a sick child.” In her meditations she contemplated and felt the suffering of mothers who had lost children, of those whose children are malnourished but lack the means to save them. Those meditations, Gosselin said “created a sea of compassion for me and all mothers who are suffering.” And she realized that she is not alone.

“My story is not that unique,” she said. “This is life…the harsh reality of life and suffering,” and feeling sorry for herself or her son, worrying about the future or what could have been done in the past, only makes her suffering worse. And while it is true that her son has a deadly form of cancer, Gosselin is grateful for “all the resources I have to support him.”

Seeing death’s face close up has convinced both Gosselin and Lyon that all they really have for sure is the present and they strive to live as fully, openly, authentically – even as audaciously – as they choose.

“I used to hold my cards close,” Gosselin said. “But after the diagnosis, I decided that I’m going to play full out. It shifted my own personal experience about how I want to live. I could be outrageous. What do I have to lose now? I could lose my son.”

When Lyon first announced his intention to hike the PCT, Gosselin’s initial reaction was incredulous. But when she realized he was serious, “I didn’t feel that I could say ‘yes or no.’ If this was what he wanted to do, he should do it.”

But as she stood at the trail head watching her son stride confidently, resolutely into a freak late season snow storm, Gosselin brought with her intimate knowledge of the years of treatments that he had endured, the myriad of toxic chemicals that his body had absorbed and the ravages they had left behind. Since his diagnosis, in words meant only for a mother’s ear, he had told her how the cancer made itself known – with pain – and that it was relentless.

Not obsessing about what might be happening to him on the trail, whether he was healthy, warm and safe, took constant vigilance and practice.

At first Lyon had cell phone coverage and would call home, regaling his mother and stepfather, Michael Gosselin, with stories of the beauty, the friends he was meeting, his first storm snug in his tent and the clear nights under the stars.

Plus Gosselin was busy, keeping her son constantly supplied with light weight, nutrient-dense, delicious meals and snacks that would also conform with his desire not to “feed his cancer” with sugary, processed foods. Food plays a very important role in the lives of “thru-hikers,” those attempting to walk the trail in one season. Lyon was constantly hungry and always fantasizing about food. Every four or five days, Gosselin would send off another package to a “drop” along the way, a country store or sometimes even a home that was near the trail. A continual river of supplies flowed from his mother, often including her son’s favorite dinners – homemade spaghetti sauce with fresh parmesan cheese, meatloaf with mashed potatoes and gravy – that Gosselin made then dehydrated in her kitchen. With a board detailing what food he had, how many miles he was likely to walk each day, what gear he needed and where it could be sent, Gosselin was the support team vital to Lyon’s success.

A month after Lyon started walking, Gosselin shopped for, prepared, dehydrated and shipped meals and snacks to three different drops then flew to Bali to co-lead a spiritual/yoga retreat.

She brought her worries with her.

A shaman, a local healer, assessed Gosselin, feeling her head, “getting in touch with my energy,” she said. He confirmed that while her physical body was strong and balanced, her mind was troubled. “He told me, ‘You worry too much’.” She showed the man a picture of her son and told him he had cancer. “He told me, ‘You don’t have to worry anymore. This is your time to let go of worry and be true to your expression on the planet.’”

In her meditations, Gosselin began to look closely at a persistent pain in her heart when she sat. “I decided to explore it. What is it?” By paying attention to it, moving towards it not away, she tapped into deep grief she was holding over her son’s plight. For days in her meditation, “I cried and cried, being with the grief.”

“I think it’s easier to have cancer than have a loved one have cancer,” she said. “A year ago I felt like I was carrying his cancer, trying to heal it. I told him, ‘You are the one who has to do the work. I will always be there but…I still have to live my life.

“I feel the best when I’m doing my own work,” she said. Besides teaching yoga and meditation to individuals, Gosselin leads group classes in both disciplines. This spring, she is leading another retreat in Bali.

“I am not helping Andy in any way by constantly being available to him,” Gosselin said. “It’s his cancer.”

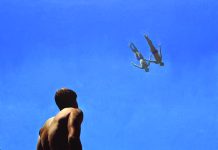

On his own, on the trail, Lyon seemed to be flourishing, often walking more than 20 miles for several days in a row, meeting fellow hikers, trail angels who left food and water for the hikers, people who sheltered him for the night and fed him fresh food from their gardens, all the while enraptured by the beauty surrounding him as he walked in benign weather through the Sierras, to Oregon and into Washington.

Then came the early morning call from Yakima, Wash., six months into the walk and 360 miles from the finish line. Lyon had left the trail after experiencing intense pain in his leg for several days. He was in an emergency room. Asked how he got there, Lyon had told the incredulous staff, “I walked here from Mexico.”

Gosselin was on the next plane to Washington. By afternoon the results of a battery of tests had come in. Lyon had a tumor on his spine. His cancer was back. “It just takes it out of you,” she said. “Then things shift and change.”

Nine months earlier a drug developed specifically for people with reoccurring Hodgkin’s lymphoma, who had already had a stem cell transplant, had been approved. Dr. Albert Brady of Yakima Memorial was one of the few physicians in the country who had it. After agreeing to administer it, Brady asked to speak to Gosselin alone. Telling him whatever he had to say could be said in front of her son, Brady insisted. “He said, ‘I just want to tell you how amazing your son is. He is so unique,’” Gosselin recalled. “It never entered his mind to tell Andy that he shouldn’t finish the trail.” And Lyon had no intentions of quitting.

The following day, after the local newspaper and television station had aired his incredible story and he’d received the new drug and a dose of steroids, Lyon was pumped and ready to start walking. Still, it was incredibly hard to say goodbye.

“I’m always so happy to be with him,” Gosselin said. “He loves me so much. He holds my hand, hugs me. He tells me he loves me and my fear falls away.”

But as Lyon and his trail buddies talked about the stretch of trail ahead, their next camp site, what they had in their packs to eat, Gosselin realized it was time for her to go, leaving her alone with her mind.

“And all the emotions come. I just watch all this,” she said. Crying as she made her way to the Seattle airport, “I realize that this is natural. I hug myself and say, ‘You’re going to be okay.’ ”

“I finally realized that I couldn’t heal Andy’s cancer for him as much as I tried. It reminds me of the last line of Mary Oliver’s poem, ‘Journey.’ ‘There is really only one life that you can save and that’s your own.’ ”

Unless asked, Gosselin doesn’t often mention her son’s cancer. When people inquire, she is forthright, simply stating, “He has cancer.” Most often, she’s composed, always elegant, very pretty and happy. She laughs easily and frequently. It’s difficult to see all the emotions, the suffering that has come and gone over the past four and a half years since Lyon’s diagnosis.

Now that her son is back, living at home, there’s been a need for a bit of an attitude adjustment. Gosselin, who prefers an orderly, clean environment, is often confronted with “Andy messes.” “Andy doesn’t pick up after himself, but I look at his mess and I think, ‘If there wasn’t an Andy mess, there might not be an Andy.’ It puts it in perspective,” she said.

Nearly every day Lyon and Gosselin practice yoga. “It really opens him up,” she said. “Sometimes he cries,” releasing the grief and the fear that he too carries. And on the days before he is set to get an infusion of his new chemotherapy drug, the pair meditate, mentally preparing, visualizing healing – and eating a large, vegan, soothing lunch served with a heaping helping of laughter.

As for Lyon’s next “big adventure,” Gosselin will support “whatever makes him happy. Isn’t that what we all want for our kids?”

“Andy and I are here on the planet together for a reason,” she said. “He came here to teach me in so many ways. He and I have always had a deep understanding, a knowing, a spiritual bond and an opportunity to evolve.

“I’m just trusting however, wherever the trail leads, it will be perfect.”

I’ve met Andy at the Vipassana retreat near Yosemite in March 2011 – we drove down to Laguna Beach with my partner and another friend and we spent 2 days at his place. We kept in touch for a while but meanwhile we moved to Australia and I don’t know anything about him. If anyone knows something please let us know.

Sadly, Andy died last August. Here is the link to the obituary. http://www.lagunabeachindy.com/andrew-lyon/