Deborah Schlesinger wishes she knew 10 years ago what she now knows about addiction. “Perhaps I could have helped my sister,” she said.

Schlesinger’s sister Jayne died at 51 from an overdose of an opioid prescribed for work-related neck pain that had become an addiction. “She failed to get treatment because she did not want it in her medical records,” the Laguna Beach resident and registered nurse said.

Terms like abuse, dependence and addict continue to stigmatize people who suffer from an illness, now known as substance use disorder, Schlesinger said. She embraces the definition in the newest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the handbook used by health care professionals, which nowcombines abuse and dependence criteria into a single substance use disorder.

A chance meeting provided Schlesinger a path to helping people like her sister. Another resident, Kathleen Burnham, recruited Schlesinger to the Collaborative Courts Foundation board.

The organization supports collaborative courts, specialized court tracks that combine judicial supervision with rehabilitation services to address the underlying issues that entangle people in the criminal justice system.

In Orange County, there are 19 collaborative court programs that help individuals who find themselves in front of a judge due to offenses related to homelessness, mental illness and DUIs as well as issues faced by veterans.

The Collaborative Courts Foundation, based in Laguna Beach, aids all 19 court programs by awarding grants for emergency housing, bus tickets, scholarships, dental work and more. “Whatever they need to succeed, we try to provide,” said Schlesinger.

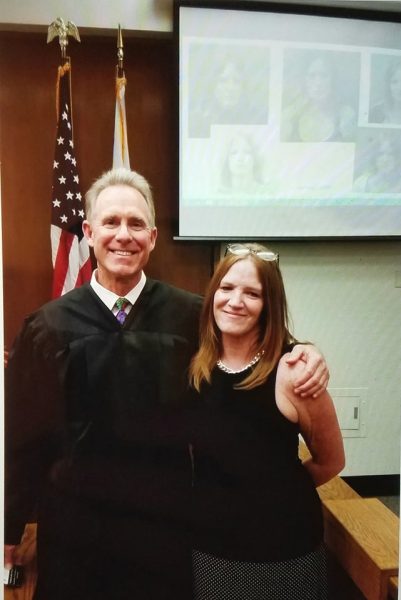

Michelle Cleary took advantage of one of the collaborative courts, entering the drug court program in 2013. She described herself as a “functioning addict.” After violating her parole on a drug possession charge, she found herself facing jail time at the age of 48. Instead, she was offered the opportunity to sign on for 18 months of drug court. “You’ve got to give it your all and there are a lot of hoops to jump through,” she said, admitting that at the start she felt resentful.

Photo courtesy o Michelle Cleary.

After violating a “no-contact” rule, she was put back a phase in the program and served a week in jail. “Even when you make a mistake they are very respectful,” she said. Despite the setback, Cleary graduated from the program in 2015.

She now works as a case manager at Nancy Clark Recoveryin Costa Mesa and says she is a “huge advocate” of the Collaborative Courts. “They maintain a zero tolerance policy, but they really care,” she said. She described drug court presiding Judge Matthew Anderson as “wonderful.”

To be eligible for the drug court program, a defendant cannot be charged with a violent crime, possession of a firearm or selling drugs. Those ineligible also include sex offenders, illegal residents or a felony DUI defendant.

The four-phase program consists of supervision by a probation officer, counseling, frequent court appearances, random drug and alcohol testing, and meetings before the judge to discuss a participant’s progress.

Noncompliance can result in essay writing, community service, jail time or ejection from the program. Positive behavior reaps rewards such as fewer drug tests and drawings for movie tickets.

Graduation requires participants obtain their high school diploma or a GED, hold a job or enroll in training or school and attend regular self-help meetings and court-related appointments.

The 19 programs in the Collaborative Court system pay off by offering life-changing alternatives to incarceration as well as significant social benefits. The system overall has saved $120.6 million since its start in 1995, a figure that reflects the absence from jail of those statistically expected to re-offend, amounting to 852,848 days of custody, according to the OC Collaborative Courts annual reportof March 2017.

In the drug court program, for example, of the 2,102 drug court graduates over the past 21 years, the re-arrest rate after three years is 28.15 percent. By comparison, the recidivism rate for similar offenders who did not participate in the program was 74 percent, the report said.

Similarly, only 9.6 percent of drunk driving offenders who graduated from the DUI court repeated the crime within five years. That compared with 21 percent and 25 percent, respectively, for second and third time DUI offenders statewide, the report said.

Participants in drug court are predominantly male, white and unemployed. Half are between the ages of 22 and 30 and half hold a high school diploma. Today, users of methamphetamine and heroin, 40 percent and 41 percent, respectively, far outnumber other participants in the program. Just 5 percent of participants are alcohol and prescription drug users.

In 2016, there were about 300 drug court participants: 136 new defendants were admitted out of over 500 applicants, 63 graduated, 50 were terminated (42 for non-compliance) and 27 left without fault, the report says.

A place in the drug court program is offered to those who the court team feels deserving; the defendant decides whether to join the program, or not. “There is no wait-list; anyone who is offered a spot can start immediately,” said foundation board member Leslie Howard, a recently retired collaborative court coordinator.

And the program’s impact goes beyond the judicial system. Over two decades, program participants gave birth to 153 drug-free babies, the report noted. Every dollar invested in the drug court at the Central Justice Center in Santa Ana saved $7.30 in other public costs, according to researchers for the California Judicial Council, the policymaking arm of the state courts.

The drug court program is state funded and administered by the county Health Care Agency. The Board of Supervisors approves the budget. The county probation department, health care agency, district attorney and public defender staff the program.

The non-profit Collaborative Courts Foundation is privately funded by grants and donations. “The organization also sponsors seminars for women on writing resumes, provides instructions for clearing criminal records, dressing for the workplace and other topics the female participants request,”said Howard.

For Schlesinger, changes in the nation’s health care system, which now require treatment for substance use disorders under the Affordable Care Act, come too late to save her sibling. “My biggest regret is, I may have been able to convince my sister to get treatment,” she said.

By supporting the foundation, she can at least provide a lifeline to some caught up in the situation that claimed her sister.

Correction:

The article ‘‘Court Program Dispenses Hope’’ in the April 8 edition incorrectly reported Michelle Cleary’s status upon entering the program. She was on probation, not parole. The writer regrets the error.

I need your help! Can you call me please? 9492053800 Thank you so much!