By Andrea Adelson

Two years ago, Pat Forster was served up an unknown chapter of his storied family history while having lunch at Molly’s Café in San Juan Capistrano.

Among the other customers to walk in that day were Harley Wick Lobo, a former Thurston Middle School math and science teacher, and his sister, Marguerite.

Forster, a nine-year Festival of Arts security guard, waved in greeting and after finishing went over to his friends’ booth to exchange pleasantries. He bantered about an upcoming Capistrano Union High School reunion. He then turned his attention to Marguerite.

Forster recalled his mother, Betty Joyce Forster, describe Marguerite’s playing guitar and singing Mexican songs.

Marguerite’s reply surprised him. She told Forster his mother and she had sung at the very first Festival of Arts in 1932. “I was aghast,” Forster said.

In the early ‘30s, the women worked together waiting tables during lunch at Tawney’s Café, near Hotel Laguna at Main Beach. Word got around town that two young gals at Tawney’s could sing really well. One of the festival organizers came over and asked the girls if they would like to perform.

Marguerite was then 17, the eldest daughter of eight children in the Lobo family, one of the oldest in San Juan Capistrano. They can trace their family history to the indigenous Acjachemen tribe, the 17th wedding in Mission San Diego in 1769 and an 1805 baptism in Mission San Juan Capistrano.

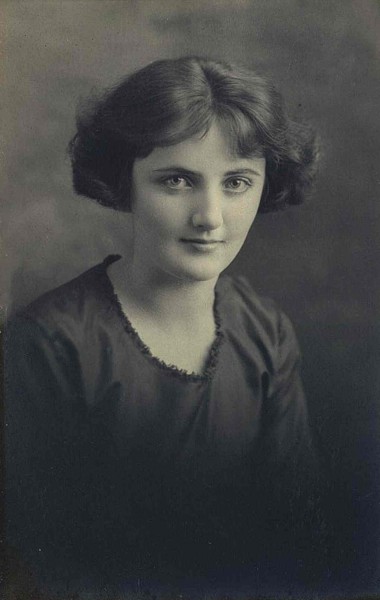

Forster’s mother, Betty Joyce, was 25 years old at the time. Fresh out of UCLA, she taught in her hometown of Capistrano during the school year and waited tables in Laguna Beach during the summer. Her family, too, originates with Capistrano’s early founders.

In 1830, Don Juan Forster left Liverpool by ship, sailing around South America and arriving in San Pedro, where he became the harbor master. He married Ysidora Pico, sister of California’s governor. He ended up owning Rancho Santa Margarita, 230,000 acres from El Toro to Oceanside. In 1845, Forster bought the San Juan Capistrano Mission at auction from the Mexican government. When a bishop complained, an order from President Abraham Lincoln returned it to the Catholic Church. The family moved out to another spot on the ranch, taking up residence near Oceanside in Forster Village, where Camp Pendleton’s commanding general now lives.

In the 1930, while Marguerite relied on Betty, who had a car, for rides to work, Betty relied on Marguerite, who played guitar, to develop fresh material for their act. The duo performed at numerous private parties at ranches and homes in Laguna Canyon. “We entertained ‘til late, late hours and then had to go to school the next day,” said Marguerite Lobo in an interview. Now 91, she still resides in Capistrano.

“I don’t remember how much I was paid. I didn’t keep it very long,” she recalled, spending it on clothing and sheet music. During the school year, she picked up pocket money packing oranges at a packing house near the Capistrano depot.

Each week, Marguerite would buy the latest newsstand songbook, which contained lyrics from songs broadcast on popular radio shows, such as the Lucky Strike Hit Parade. She would also copy down by hand the lyrics sung by other performers, though she relied on her ear to reproduce the music. In grammar school, instruction had included learning to read music.

Her real musical education, though, came at the knee of her mother, Hope, a violinist. She led a band that included a trumpeter, saxophonist and drummer that played in Capistrano’s downtown hotels, which no longer exist. “I used to look forward to that,” Marguerite said. The hotels also attracted touring companies from Mexico, which brought dancers as well as singers and musicians to perform. “They took little nips now and then,” she remembered of the musicians, conduct that was risqué during prohibition. “I would hang on the fences,” she said, and try to commit the choreography to memory. Her mother, too, would incorporate the repertoire of the visiting musicians into her own group.

So when the girls were asked to sing at the new fangled festival, they were seasoned performers. Marguerite recalls the pair wore costumes and sang in-between set changes, meaning they actually may have performed in the second festival, but the first pageant, which was held in 1933. The girls sang “La Paloma,” “Allá En El Rancho Grande” and “Cielito Lindo,” in Spanish, with Marguerite accompanying them on guitar. “I liked the Mexican music because it had a different rhythm,” she said.

Being multilingual then was unique, said her brother, Wick.

“I went whenever they called me because then my mother wouldn’t say anything,” said Marguerite, whose mother was confined to bed in her 30s because of tuberculosis. For years, her daughter continued to perform, playing at a local USO club and for several different big band orchestras.

Evelyne Lobo, a younger sister, also apparently sang at the pageant. She is mentioned in a 1940s column called Decades written by Doris Dunwood in Capistrano’s weekly newspaper, the Coastline Dispatch. Dunwood’s column recounted events from previous decades, noting “a new voice find from Capistrano” that performed at the festival.

In 1935, Betty married Marco “Tom” Forster and the couple had three children, sons Tony and Pat, and a daughter, Jo Jo. Betty died in 1977.

Pat Forster and his children, Jens, Larry and Ann, have all worked on the Festival’s security detail. They are rightfully proud to discover a Festival pioneer among their pioneering ancestors.