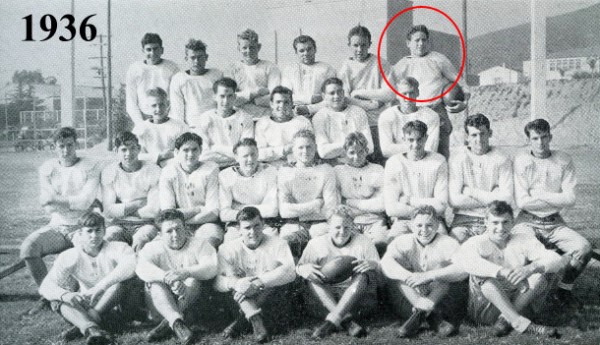

On a late October day in 1936, Laguna Beach High’s football team held a slim 2-0 lead over their Orange league rival Tustin High. The Tillers were driving for the go-ahead score against an undersized but tough Artists defense, when junior defensive back Art Sherman stepped in front of a Tustin pass at the 40-yard line and returned it 60 yards for a touchdown. “They were moving the ball well, said Sherman recently. “That broke them up pretty good.”

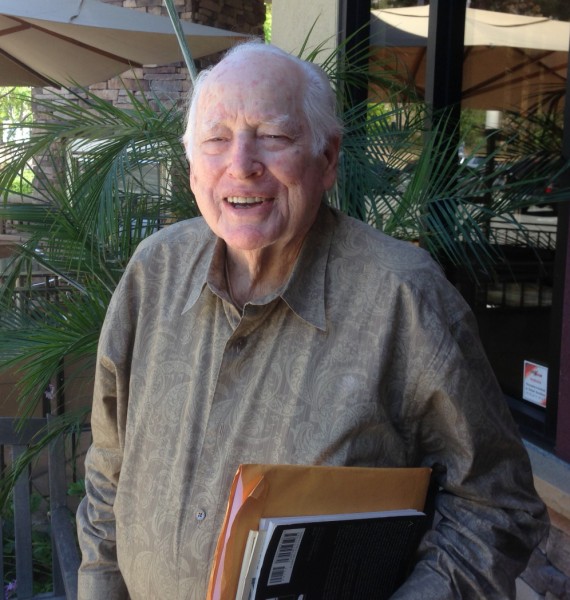

The win catapulted Laguna to their first league title in only their second season in existence. Sitting on the concrete bleachers overlooking the field of artificial turf that now bears the name of his former high school coach Maurice “Red” Guyer, the 94-year-old Sherman recounted the play like it happened yesterday.

“I can remember it real well. I picked him off right there,” Sherman said, pointing to the 40-yard-line on the home side of the field. “I remember running over and curling back,” he continued, waving his arm across the field toward the ocean.

“I remember some of the guys running and jumping on me,” he said with a proud smile, pointing to the far side of the west end zone where he scored the only touchdown of his three-year varsity career.

Of course in Sherman’s day, the field was grass, the stands were made of wood, and Guyer, the school’s first athletic director, had just begun the unenviable task of building a respectable athletic program at a new school of less than 200 students. “Red Guyer was the coach,” said Sherman, emphasizing “the.” “He had a little temper, but he was fair.”

Sherman’s family was hit hard by the economic collapse of 1929. His father lost a pottery business, his Santa Barbara restaurant, and eventually the custom family home he had built in remote Laurel Canyon north of Los Angeles.

Later that same year, Sherman’s father moved his family to Laguna, where rich people and celebrities were building second homes. He hoped to find opportunities where he could leverage his skills as a craftsman and landscape artist.

And though times were hard, the young Sherman instantly fell in love with his new home by the sea. “I bless my dad every day for having moved down here. It couldn’t have been more wonderful.”

That first year in Laguna, Sherman watched in awe as a crew moved the town’s iconic lifeguard tower across Coast Highway from the Union Pacific Oil gas station to its current location at Main Beach. At night, he and his friends would often roam the unguarded halls of an unfinished Hotel Laguna, sneaking up to the cupola to throw water balloons at passers by.

Times were different back then. Unchaperoned Laguna kids would play sports on any open lot they could find or explore the pristine waters that lapped the rugged undeveloped coastline. “We were beach rats, you know, and grew up body surfing mostly,” Sherman said. “As long as you were home for dinner.”

Sherman’s longevity is probably best illustrated by the fact that, as a young teenager, he participated in one of the first Pageant of the Masters, which is celebrating its 80th season this year.

Because Laguna Beach High had not been built when Sherman graduated eighth grade in 1933, he had to make a choice between Newport High and Tustin High. He chose Tustin because he played beach volleyball with a lot of the guys from that area. But his girlfriend at the time chose Newport, and later went on to marry the son of a former Newport mayor. “That was a bit of a joke on me,” he said laughing.

Laguna Beach High opened the following year on the site of Sherman’s old “grammar school” and he would graduate with the class of ’37.

Sherman’s quick feet and smooth moves weren’t confined to the gridiron. You could often find him with his favorite dance partner at Balboa’s Rendezvous Ballroom, doing the Balboa Shuffle. “We used to bet the band we could dance as fast as they could play,” said Sherman.

To fulfill his one-year military service requirement, Sherman volunteered for the Army. A month before his year was up, Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Sherman served as a member of the 40th Infantry Division. His unit was assigned to various posts along the southern California coast, including the Santa Monica Pier, San Luis Obispo and Goleta near Santa Barbara, where a Japanese submarine shelled an oil facility near the coast. “We were the only troops fired upon in the continental United States,” said Sherman.

While patrolling the Santa Monica Pier, Sherman met his future wife, a surfing beauty who was a “favorite of the local lifeguards,” he said.

They were married during a hastily assembled ceremony the night before Sherman shipped out for Hawaii. They had a daughter and later divorced.

Sherman delighted in training new recruits while stationed on Kauai. He would set up obstacle courses and design exercises that were nearly impossible. “It was like football all the time. Go. Go. Go,” said Sherman. “Most of the guys couldn’t get their butts off the ground,” he added laughing.

The clear blue waters that surrounded Kauai called to Sherman, but wartime regulations made swimming strictly forbidden. “God that was tough,” said Sherman. “Couldn’t even touch your toe in the water.”

These days Sherman makes his home in Mission Viejo. He still follows the Breakers, although he scoffs at the school’s decision to change its name in 2003 because Artists didn’t sound tough enough. Said Sherman, toughness comes through on the field, not through some silly name.

Even so, as he watched the 80th iteration of the team running plays on the plastic grass in front of him, he appeared to like what he was seeing.

Frank Aronoff contributed to this story.

[…] 25, 1934 at Valencia and the first home game on old Laguna Field on Nov. 8, 1934. Art Sherman, who was profiled in the Indy, was one of the few players still living from that […]