School board incumbent Bill Landsiedel’s characterization of challengers Tammy Keces and Dee Perry as single-issue candidates has transformed a PTA garden project into an unexpected political hot potato.

Asked to support his allegation in a video interview with the Indy, Landsiedel cited as an example the proposed outdoor classroom and teaching garden at Thurston Middle School supported by Perry, despite the fact that after two years in development it was rejected by district administrators last spring.

Landsiedel described the project, which was never formally considered by the school board, as too expensive and lacking broad support from staff and parents. That elicited an uproar from parents involved, who are now challenging the veracity of the incumbent’s claims.

Even so, PTA minutes and district records as well as garden committee reports over the past two years show that advocates received mixed signals about the classroom garden’s viability from PTA leaders and two successive principals. Even as top administrators warned the PTA as early as October 2011 against initiating new projects due to fiscal uncertainty in the district, project workers were being advised by administrators to tweak their plans for further appraisal.

Landsiedel said the project’s initial $300,000 price tag would have inflated to an estimated $500,000 as a result of anticipated requirements pointed out by the district’s former facilities director, Eric Jetta, information never fully aired with proponents, they say. Landsiedel, seeking re-election to a second four-year term on Nov. 6, said he supports Supt. Sherine Smith’s decision that the initiative was too costly and could not be a priority.

Prior to its formal rejection, “No one ever said ‘no’ to this project” over the course of two years of plan refinements prompted by suggestions from administrators, said parent and PTA member Lori Levine, who wrote the project proposal. She collaborated with a PTA committee that received input from Principal Joanne Culverhouse and later her successor, Jenny Salberg.

But Levine confessed she was shocked by what she saw as Landsiedel’s misrepresentation of the project, also in the video interview. “The project was a gift to the school, funded by grants, donations, and $25,000 that was already banked,” she said. And her proposal accounted for every single budget item to support the garden, including ongoing maintenance. “I am not part of a special interest group. I have funded no candidates,” she said, in answer to another blanket accusation Landsiedel made on his website and since removed in reference to his challenger’s supporters.

Similarly, parent Wendy Proudlock-Meyer, who spent countless hours designing the classroom and garden, revising plans and projecting its budget, conceded that she was “totally dumbfounded” by Landsiedel’s portrayal of the project as too expensive and lacking support. She calculated its cost at $150,000, which was to be funded privately through fundraisers and donations.

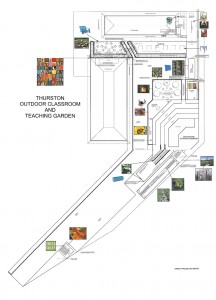

The project was be located near the existing outdoor campus amphitheater and would include a solar food dehydrator, a weather station, fruit trees, pollinator plantings to entice bees, a fragrance garden, an edible organic garden, a greenhouse built of recycled water bottles, rain barrels and a stand to sell the garden’s bounty.

In a follow-up interview, Landsiedel said his conclusions about the garden were gleaned from a PTA presentation and informal talks with the facilities director. He also knew that special permits required by the state architect would likely be required and anticipated other bureaucratic procedures could incur further costs.

The pledge of private funding did not lessen the district’s responsibility, financial or otherwise, he said. “We do not allow gifts where the donors say they want a particular construction project done unless it is vetted with the district staff, the superintendent and the school board votes to accept the terms of the gift.”

In the current fiscal environment, “where we are fighting to maintain class size reduction, we would not spend money for a project unless it was a priority of the district, even if the money was all privately donated,” he said.

The superintendent cautioned that the district would “ultimately be responsible for all costs, despite the good intentions of possible donors and volunteers.” Pointing to the district’s funding losses in the previous five years, Smith said, “it is our obligation to be fiscally prudent as stewards of the taxpayers’ dollars; this project would have been expensive and involved much staff time.”

The seed for the garden sprouted in 2010, planted by health teacher Penny Dressler. PTA president Lynn Gregory endorsed the concept, Proudlock-Meyer was enlisted to draw up plans and Levine was asked to draft a full proposal, with a budget that included ongoing maintenance. In that first year the committee received detailed input from teachers across disciplines about how they might use the space.

Meeting minutes show the project gained momentum and support. “We had so many parents, students, and organizations onboard it was hard to keep track; there were those with a check in their hand, and those with a shovel,” said Levine.

But last October administrators began to express concern over the project’s scope, its impact on staff time and unknown costs that might crop up. Even so, Proudlock-Meyers, Levine and others moved forward and discussions with Salberg and Jetta continued. Interest in the project, though, seemed to flag as leadership in the PTA and the principal’s office changed last year.

For her part, a frustrated Dressler can’t understand how “a really good idea for our students can become so crazy.”

“It was never meant to be political,” she said. “It’s nobody’s fault. It’s that the voices are not sitting in the same room together having a conversation.” Meanwhile, there are a lot of parents who made a commitment and who are disappointed, she said. “In the end, I really hope that something gets done and that the kids have the community behind them.”