![]() By Mark Chamberlain, Special to the Indy

By Mark Chamberlain, Special to the Indy

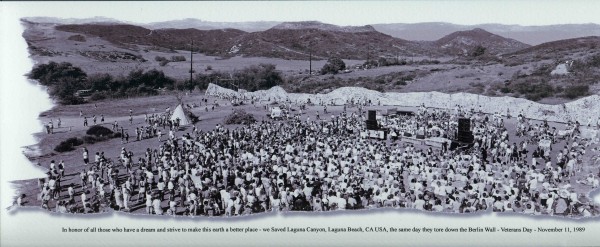

Veterans Day is a special day of remembrance for many in Laguna Beach and Orange County because the federal holiday also coincides with the anniversary of the famous Laguna Canyon walk, a critical turning point in the battle to shield Laguna Canyon from development.

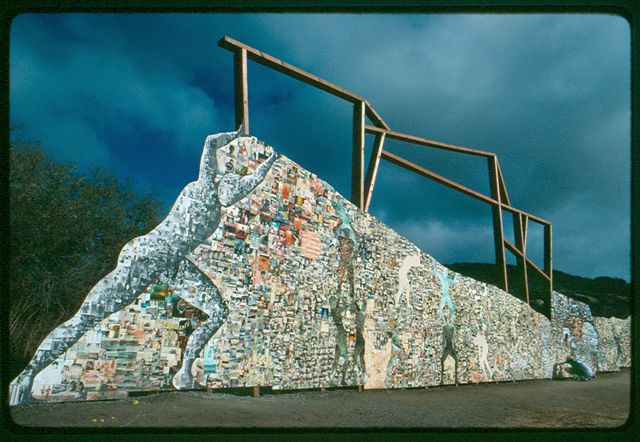

Sixteen years ago on this day, thousands of concerned citizens turned their back to the sea and walked into the canyon to express their belief that this beautiful gateway to the Pacific Ocean and Laguna Beach should be spared the urbanization sprawling across Southern California. For myself and my partner, Jerry Burchfield, along with many cohorts induced to participate in an unusual civic art project, the day also was the culmination of a decade of work and the completion in glorious fashion of The Tell, a mountainous photographic mural that was the walk’s destination.

The Tell was Phase VIII of the Laguna Canyon Project, begun in 1980 when for the first time we sequentially

photographed the canyon’s entire nine-mile length between the freeway off ramp and the ocean. Then, plans to transform this bucolic two-lane country road into a major artery, bisected by a toll road with development along its path, seemed inevitable. Our original goal was to document the road as it was both before and after. If nothing else, at least museum patrons would get the chance to view the photographically preserved pathway, which was crucial to the identity and character of our home. It would serve as dramatic evidence of how we dealt with the “last nine miles of our westward migration.”

Along the way, we came to realize that our activities themselves were creating greater interest in the fate of the canyon. Along with providing perhaps the most complete documentation of a region ever undertaken, each successive phase of the project generated greater public awareness and involvement in the plight of the region. The Tell was no longer just another art project for museum walls or historical archives, but performance art with the capacity to make a difference in the ultimate outcome.

“Field of Dreams” was a phenomenal hit when it was released that year, and “if you build it, they will come” entered the vernacular. The year 1989 was also the centennial of Orange County and the sesquicentennial of the discovery of photography. To mark these events, we managed to gain permission to construct the largest photographic mural ever made. It was to be located in Sycamore Hills, at the crossroads of the then-proposed San Joaquin Hills toll road and opposite the Irvine Company’s proposed Laguna Laurels housing project. We built it, invited them, and they came.

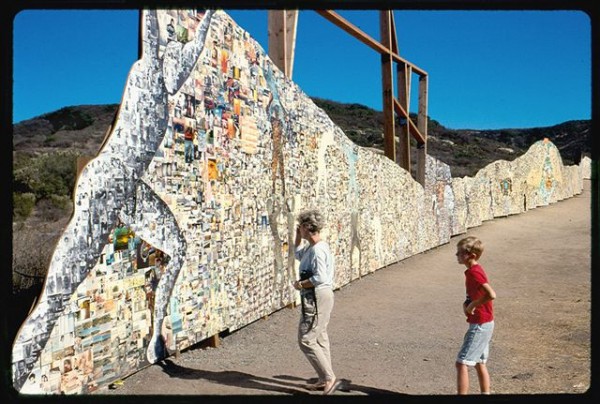

After three years of planning and months of fundraising, the project was awarded a timely Festival of Arts grant. Other support came from the City of Laguna Beach, the Laguna Canyon Foundation and myriad individual donors. With these resources and our growing army of supporters, on May 1, 1989, we began to build a 636-foot long mural comprised of over 100,000 photographs. The images were contributed by hundreds of people from all over the country concerned about the canyon’s fate. With this giant sculpture, we were building a contemporary mound of artifacts, what anthropologists call a tell, that would reflect the past and future.

Over months of construction, the mural lived up to our hopes and indeed became the focal point and even catalyst for numerous events and demonstrations. Some were planned and many spontaneously happened. For the Aug. 19 dedication to celebrate the actual “birthday” of photography, over 2,000 people attended, along with scores of environmental groups from around the county. Lured by almost daily coverage by regional media, soon national publications discovered the topic. Life magazine featured a piece on the mural and its message in its Woodstock 25th Anniversary issue. Then, network and cable news organizations started expressing interest, hinting at coverage of a planned Veteran’s Day Walk on Nov. 11. Nevertheless, the huge public turnout that proved a critical turning point in winning protection for the canyon did lose out to the top news story of the day: the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The Veteran’s Day walk won official sanction of Laguna Beach through the efforts of the late Lida Lenney, mayor pro tem and leader of the Laguna Canyon Conservancy, and Martha Collison, who championed The Tell before city officials. Irvine’s Mayor Larry Agran, that city’s Conservancy, Laguna Greenbelt, Village Laguna, Save our Shores, and other county environmental groups, also endorsed a canyon walk. All factions were orchestrated by walk coordinator Harry Huggins.

The efforts were just in time. This was not only the 11th day of the 11th month, but the 11th hour. The county Board of Supervisors was scheduled to approve the building of the Laguna Laurel housing project the very next Tuesday.

Although official estimates varied widely, nearly 11,000 people marched the canyon, hiked over the hills, and bicycled to Sycamore Flats to express their desire to keep the canyon free of development.

Largely as a consequence of this dramatic public demonstration, Donald Bren, owner of the Irvine Company, ultimately agreed to sell the land and, in the next year’s election of 1990, the residents of Laguna Beach turned out in record numbers to overwhelmingly vote to tax themselves to purchase the land to keep it as open space in perpetuity.

Yet, the public demonstration did not succeed in defeating the six-lane toll road, which was completed in 1996. But where another city was going to be built is today the Laguna Wilderness Park. Sycamore Hills, where The Tell once stood and a final stand took place in dramatic fashion, is now the site of the Jim Dilly Preserve.

[…] recapped events for Indy readers in two Laguna Home Companion stories in 2005. See the links for Tell Tale 1 and 2 at […]