Fred Sheldon wasn’t a bad student, just bored, so getting by was the best he did. He didn’t fit the rote routine of school. Sheldon was fading into nowhere, his creativity untapped.

Until he learned how to blast off a bottle rocket, and get credit for it.

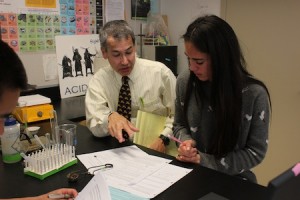

Pegged as an “average” student, Sheldon was fortunate enough to fall into science teacher Steve Sogo’s honors chemistry class during his junior year at Laguna Beach High School. He asked Sogo if he could put hydrogen and oxygen in a glass soda bottle and light it on fire.

Sogo said okay, and they took the bottle outside to the high school’s quad, no blowing up the lab here. They mixed the compound, using a magnesium strip for a fuse, lit it and watched.

“I thought it failed,” said Sogo, “a good idea, but nothing.” Until they went to retrieve the bottle. “Then it went off, it went boom and it flew into the air. We were in the unknown. That was the most exciting, the unexpected.”

He said the “rather explosive” experiment has morphed into a regular rocket lab each March, which evolved from Sheldon’s inquisitiveness in 1991. Continuing his trajectory of engaging borderline students, Sogo was selected last week as one of only three K-12 teachers nationwide to receive the 2013 National Science Teachers’ Association’s award for excellence in student-inquiry-based teaching.

Navigating real technological systems has become part of Sheldon’s daily routine. He went on to earn a degree in math with emphasis in physics at Humboldt State University. He quickly landed a job at Boeing in Huntington Beach, where he’s worked for 15 years, now heading up the advanced technology department for unmanned underwater vehicle development. Not bad for a student once without game.

“There’s no reason a high school student can’t do groundbreaking research,” said Sheldon, a concept he embraced from Sogo’s confidence-boosting approach to teaching. “That’s the best way to demonstrate how he’s set apart from the traditional science teacher, or teacher period. At the time, I would say people had low expectations of me and he proved to me that they’re wrong.”

Sheldon credits Sogo as the first teacher to recognize his potential, letting him work at his own faster pace. “School can get kind of boring, and when you have someone feeding and watering you, so to speak,” he conveyed, “it really made things a lot more interesting. It was my number one class of all time, including everything I’ve done in college.”

Sogo’s NSTA award was co-sponsored by the School Specialty Science Group, which publishes “learning by doing” science curriculum and sells lab equipment science brands, including Frey Scientific products. He was also only one of six teachers in California and 32 nationwide to receive an elite award in 2003 from the Amgen Foundation, the charitable division of a Fortune 500 biotech company, for his dedication to inspiring future Nobel Prize winners. He was presented with a $10,000 check.

“His most valuable asset,” said high school principal Joanne Culverhouse, “is his ability to develop experimental and analytical skills in his students. The (advanced) class he actually wrote and designed.” Culverhouse said Sogo’s organically creative approach and focus on each student’s learning pace sets him apart from other high school teachers in the county.

“Many of my best students have been kids with very low GPA’s,” Sogo recounted. “They were the ones who did not thrive in the rote, memorization, there-is-one-answer-learn-it environment. But they really did thrive when they were given the freedom to explore and create because that was their strength all along. They’re the out-of-the-box, creative, I-don’t-follow-the-rules type of person.”

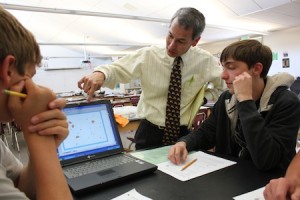

Sogo’s academic claim-to-fame is his passion to get students in a hands-on, figure-it-out-for-yourself mindset. “I come in with the idea that creative thought is the most valuable skill,” he said. “I don’t care whether you know an answer. I care whether you can think about how to get an answer.”

He offers his students “game scripts” drawn from film, television and novels to solve scientific mysteries in his labs, and they rarely text their friends the answers. “The ethos of the classroom is the fun of doing it yourself,” relayed Sogo, “to figure out your own solution.”

After earning a master’s degree in chemistry from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena in 1989, Sogo abandoned his research project as a Ph.D. candidate when an instructor made a simple prophetic statement, “You should do something important.” Sogo had the thought, “Do what you like to do and good things will happen.” He’s doing that and they’re happening.

His first teaching job was at LBHS in 1989 until he left in 1992 to try a few other places. He returned to Laguna in 2001, and is considered a hard teacher. “I had a student who said that his biology class was just hard and no fun,” Sogo recalled, “and he had another class that was just fun but said, ‘We don’t learn much.’ Mine was the class where it’s hard but it’s fun. There’s value in the learning. That was very gratifying to hear that.”

Sheldon remembers Sogo’s “MacGyver” days where students were handed a script modeled after the secret-agent television series. They outlined an adventure needing scientific discovery with steps that would draw students through a maze of twists and turns.

One particular problem was figuring out how to get through a locked door selecting possible problem-solving tools; in this case, a pile of gray stones, a wrench and a bottle.

It turned out that the pile of gray rocks, when mixed with water, produced an extremely hot gas able to melt through metal, i.e., a door lock. “It was brain gymnastics at its best,” said Sheldon. “It captured a lot of us into being excited about thinking.

“Usually when you’re in class, you’re going to travel at one pace, and that’s the pace of the curriculum, even if you’ve already got it down. I was a kid at the time and I didn’t have full realization that if I wanted more, I could go seek it out myself. That was something he showed me.”

Sogo’s current frontier is bringing nature into the classroom, inspired by close friend Terry Collins, a global sustainable science proponent and professor and director of the Institute for Green Science at Carnegie Mellon University.

“I’m a big proponent of green chemistry,” said Sogo, who spent three days of spring break hiking and “taking pictures of lizards” in Joshua Tree National Park with his wife Farah and their son, Jeremy, 14 (their other son, Alexander, 19, is at Brown University). Science, he said, can find ways to fulfill modern society’s demands with minimal environmental impact. “That’s certainly something I have incorporated into my advanced chemical research class,” he said. “We’re smart enough to make it better.”

Photos by Solveig Erngren

[…] cutting-edge experiments and opening enrollment of a chemistry class to students of all levels earned the campus a 2017 Gold Ribbon Award from state education officials […]