The James Dilley Greenbelt Preserve, named after the quintessential bookshop proprietor and ultimately effective environmentalist, may soon get its just rewards.

That is, if four men with a common passion for wild spaces have anything to say about it. And they just might. All of them have done this type of thing before.

Driving in or out of Laguna Beach along Laguna Canyon Road is considered one of the most picturesque routes in Orange County. Undeveloped coastal sage-scrub hillsides are a welcome sight, even in bumper-to-bumper traffic, that relieve the eye and soothe the soul as they lead travelers seaward.

Except when the route passes the James Dilley Preserve, formerly known as Sycamore Hills, just north of the 73 toll road. Gateway to the 376 acres of wilderness and hiking trails, the preserve is bordered by a chain-link fence and a gravel parking lot anchored by a dumpster and porta-potty. It’s a “visual blight,” say the four greenbelt advocates, and not befitting of the Herculean efforts of one man, the legend who started it all.

The vision and talents of landscape architect Bob Borthwick, wilderness docent John Monahan, conservationist Scott Ferguson, and planning commissioner and landscape architect Roger McErlane converged to create a blueprint honoring the first parcel of land that “saved the canyon.”

“Thousands of people visit Laguna Coast Wilderness Park every week,” said Monahan, who leads weekend geology hikes, “but the majority of them have little idea of the incredible efforts that were made to create the greenbelt around Laguna Beach.” Monahan decided the preserve’s “staging area” was not worthy of its namesake.

Improving the Dilley Preserve was part of Borthwick’s plans to restore Laguna Creek to a healthier state along Laguna Canyon Road. The conceptual plan was unanimously approved by the City Council a year ago. The city owns the property, which it purchased in 1979, but the Orange County Parks Department manages it. Plans would need parks department approval, said Scott Thomas, OC Parks design manager.

The initial plan has received the support of local environmental groups such as Laguna Greenbelt, Inc., and the Laguna Canyon Foundation. It calls for a larger shade shelter and education staging area, and a meandering stand of native sycamore and oak trees that will provide their own canopy of shade, explained Borthwick.

“It’s low key,” said Borthwick, “understated in a classier, more natural way than what’s there now.” All materials, he said, will be environmentally sustainable.

A plaque telling Dilley’s Laguna Greenbelt story will be showcased. Fencing farther off the

road that blends with nature and keeps wild animals from crossing traffic, improved restrooms and an enclosed dumpster have also been penciled in.

“The accomplishment of Dilley and the beauty of the site and importance of the greenbelt needed a more…inspirational focus,” said planning commissioner McErlane. “So other than just correcting the Caltrans image, we needed a more inspirational and iconic structure, located to represent the open space that we have and the trail head that provided access to it.” With input from Monahan, McErlane elaborated on Borthwick’s plan for the preserve. The plan will be used to initiate conversations with the county as well as Caltrans and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

It will take $500,000 to upgrade the preserve’s entrance, says Borthwick, who hopes to tap Ferguson’s experience in raising funds for land conservation.

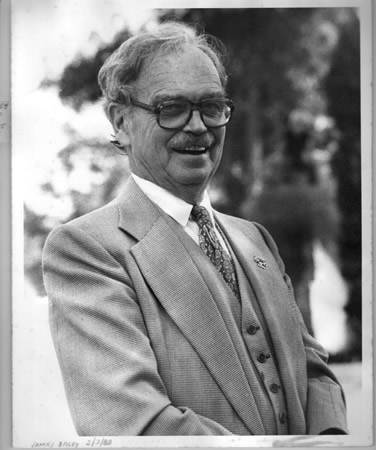

The legendary man, Dilley, remains regarded as a dilly of a character and respected, before and after his death, as the father of the greenbelt. Dilley owned Dilley’s Books and later founded the nonprofit Laguna Greenbelt Inc. to organize efforts to keep development from encroaching on Laguna Beach. He was worried that the geographically protected beachside town would be “inundated with the sprawl and Laguna would lose its separate identity,” Ferguson said.

Ferguson said he worked closely with Dilley on the Greenbelt board of directors for eight years before the disheveled open-space pioneer died in 1980, noting that Dilley was always candid about being a recovered alcoholic and his battle with Parkinson’s disease. Ferguson spoke about Dilley at the Greenbelt’s annual meeting last month, nearly channeling the man in voice, posture and skeptical gaze over the top of his spectacles as they slipped down his nose.

He was “an environmental rebel against the titans of development, including the Irvine Company and Philip Morris, the tobacco company that had purchased the former Moulton Ranch to create the new town of Aliso Viejo,” Ferguson said.

Laguna Beach purchased Sycamore Hills, then 521 acres, for $6.7 million after the City Council’s unanimous support and a threatened lawsuit by developers with plans for a golf course and homes. Later, 144 acres were sold to the county for a regional park and the 73 toll road, and to a developer, according to city open space acquisition records.

Mayor Steve Dicterow has yet to see the plans for the preserve, but he and council member Kelly Boyd will soon tour the site with Borthwick and Monahan, who already showed the site to the other council members. “I’m hoping to be very delighted by it and I’m hoping to be very supportive,” Dicterow said.

Dilley served as the inspiration behind the Laguna Canyon march in 1989, 10 years after his death. Nearly 8,000 people protested another development, the Irvine Company’s proposed Laguna Laurel project of houses, hotels, golf course and office space. As a result, 22,000 acres became the South Coast Wilderness Preserve, which includes the 7,000-acre Laguna Coast and the 4,500-acre Aliso-Wood Canyons wilderness parks. All of it is managed by the County of Orange.

The Dilley Preserve was the first parcel of land set aside as permanent wilderness in Laguna Canyon.

As the earth-shaking influence that got the whole thing started, it is fitting, say the men behind the plan, that the preserve reflect the depth and unflailing efforts of a man who devoted his life to keeping Laguna Beach surrounded by the wild and free.

Brains first and then Hard Work.

A. A. Milne

[…] Advocate May Receive His Due on Land He Preserved […]

[…] to upgrade the entry to the Dilley Nature Preserve, 376 acres of wilderness off Laguna Canyon Road north of the 73 toll road, at $125,000, presented […]

[…] star of the film, Jim Dilley, a bookstore owner and founder of the open-space advocacy group, motivated thousands of people to […]